Brazil is dealing with a massive corruption scandal, incomplete Olympics preparation, and an outbreak of Zika. But some would rather have the country concentrate on the ills of Israel instead.

On November 29, 1947, Brazilian diplomat Oswaldo Aranha presided over the General Assembly of the United Nations during the vote over resolution 181, which called for the establishment of two states, one Jewish and one Arab, in Palestine. Brazil voted “yes,” thus taking an active role in the establishment of the State of Israel.

Today, however, relations between Brazil and the Jewish state are less than stellar, reaching a new low last year, when the Brazilian government informally rejected Israel’s newly appointed ambassador, Dani Dayan, based on his positions regarding the two-state solution.

This hostility toward Israel has largely been the result of political changes in Brazil itself. In 2002, the left-wing Workers’ Party rose to power. The economy grew considerably, with the party’s policies helping millions of people rise from poverty and enter the working class. But like much of the Latin American Left, it has also been greatly influenced by radical Palestinians and their supporters. And it is not alone. Anti-Israel groups have managed to find an intellectual, academic, and political home within many left-wing social and political movements in Brazil.

According to the narrative embraced by many on the Brazilian Left, Israel is an oppressor, an illegitimate country, and the occupier of a Palestine that encompasses all the land from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. It is not a coincidence that in the 2010 presidential elections, Brazilians living in the Palestinian territories voted for Workers’ Party candidate Dilma Rousseff, while those living in Israel voted for her opponent.

This is, of course, a reflection of international trends, particularly in Western Europe. But there is a major difference: Due to the party’s political success, individuals and groups who embrace the anti-Israel narrative have become influential activists, academics, intellectuals, and government officials, particularly in the educational system. Taking advantage of universities and institutions with high social visibility and the capacity to mold public opinion, they regularly engage in anti-Israel propaganda. The result is catastrophic for Israel’s image.

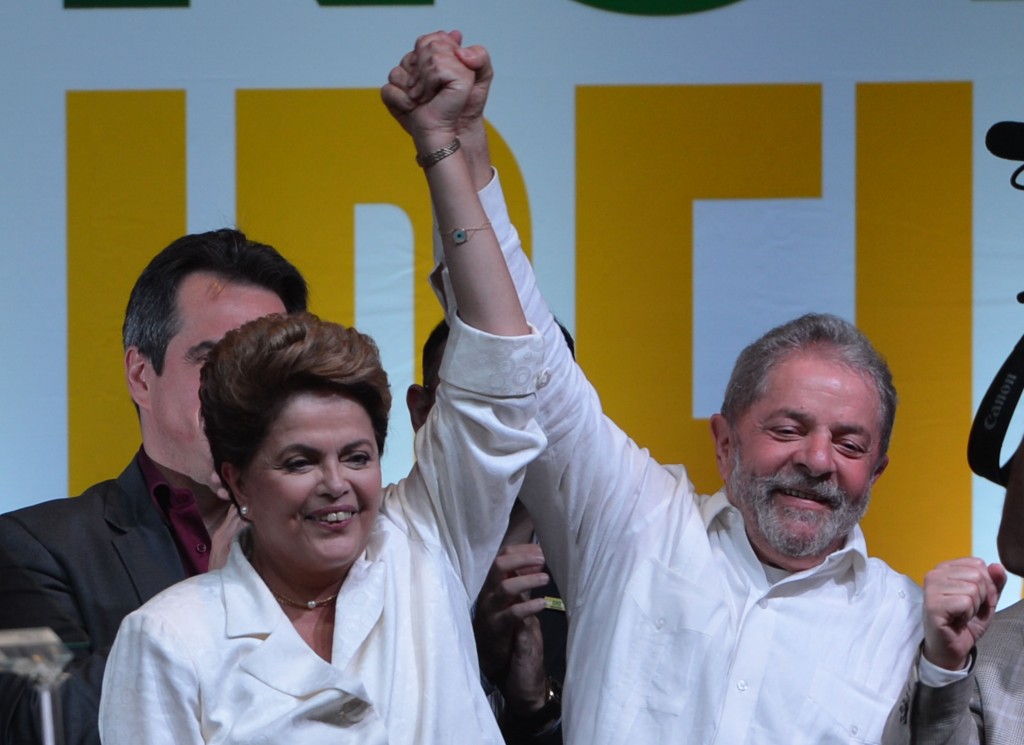

Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff (left) and her predecessor Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva celebrate her re-election victory, October 27, 2014. Photo: Fabio Rodrigues Pozzebom / Agência Brasil / Wikimedia

Salem Nasser, for example, is a professor of international law at the Getulio Vargas Foundation, a leading university in São Paulo, Brazil’s biggest and most important city. Nasser is regularly consulted by GloboNews, the main Brazilian news channel, for commentary on terrorism and Israeli affairs. He is also president of the Brazilian Arabic Culture Institute, for which he often pontificates about Israel and the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in articles like “68 Years of Nakba” and “BDS against Apartheid in Palestine.”

Another prominent anti-Israel academic is Reginaldo Nasser (no relation), a well-known and influential professor of political science at PUC University in São Paulo who has helped promote “Israel Apartheid Week.”

Perhaps the most vicious and openly racist anti-Israel activist in Brazil is Carlos Latuff, a globally-known cartoonist who was ranked second on a list of influential anti-Semites by the Simon Wiesenthal Center. He is well-known for pushing his anti-Zionist, anti-American, anti-capitalist, and anti-war beliefs through his work. His anti-Israel cartoons made headlines during the last Gaza war due to their explicit images and hysterical rhetoric. He also won second place in Iran’s International Holocaust Cartoon Competition.

These figures are, of course, just a few examples. But they express views held by a great many involved in Brazil’s countless social activist and leftist groups, as well as the Workers’ Party itself. But why has anti-Israel sentiment proved so popular?

In some ways, the answer is simple: It is at least partially based on economics. Throughout its history, Brazil has fostered massive economic inequality, with a poverty-stricken majority and a super-wealthy elite. This has led many to see the world as a Manichean struggle between the evil rich and the virtuous poor. Due to the stereotype of the Jews as wealthy, this can quickly lead to viewing the Jews as a force for evil. This ideology of class struggle also has an international aspect: The identification of the United States with the evil rich. Since Israel is a strong ally of the U.S., this can lead to the conclusion that “the best friend of my enemy is my enemy as well.”

This hostility toward Israel has recently taken a dark turn, attacking the legitimacy of Israel’s existence in and of itself. These vaguely genocidal sentiments are not confined to the lunatic fringe, but have been voiced by many important politicians and public figures in Brazil, with diplomatic consequences for Israel.

For example, during the 2014 Gaza war, the Brazilian government recalled its ambassador to Israel for consultations, but did not do the same with its ambassador to the Palestinian Authority. During the war, Marcos Aurelio Garcia, President Rousseff’s former Special Advisor for External Affairs, described Israeli military actions as a “massacre” during a television interview.

This has inevitably resulted in the rise of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement in Brazil.

BDS came to Brazil in organized form about six years ago. Its most important leaders are Israeli-born, Brazilian-raised siblings Yuri and Yara Haazs. Last year, Yara visited singer Caetano Veloso in an attempt to convince him to cancel a performance in Israel, bringing him letters from Roger Waters and Desmond Tutu. The attempt failed and the show took place. But once in Israel, Veloso was given a tour of the West Bank by the NGO Breaking the Silence. The ultimate result was a victory for BDS. Veloso later wrote an extensive article in Brazil’s leading newspaper saying,

After receiving the letter from Roger Waters and Desmond Tutu and the visit of the young BDS representative, I began to research more about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Upon returning from Israel, I also received many emails with videos from Breaking the Silence in which a Palestinian was beaten with pieces of wood by Israeli settlers. … I miss Tel Aviv. For me, it is like Bahia, it is my place, but I believe I will never go back.

The boycott movement in Brazil has not been as successful as it has been in some European countries or even the United States. In Brazil, issues regarding Israel are less prominent in the media and academia. Israeli academics and politicians do not visit Brazil frequently, leaving BDS with fewer targets. Nonetheless, the movement has begun to get more and more attention from the national media and thus the Jewish community.

In the academic field, BDS hate groups succeeded in convincing 200 professors to sign a petition in support of the movement. More famously, in 2015, Santa Maria University made headlines due to a note written by the vice-dean of the university, Jose Fernando Schlosser, in which he asked the staff of the master’s degree program to provide the names and courses of Israelis currently attending the school.

The original request had been sent to the vice-dean by pro-Palestinian groups after it was revealed that the university was involved in a defense technology project jointly undertaken by the Brazilian company AEL and a subsidiary of the Israeli company Elbit. It asked to clarify, among other things, whether the university has “any plans or intentions to promote initiatives linked to Israeli companies, public entities, or professors, even through its subsidiaries in Brazil” or if “there is any intention to receive, in the near future, professors, students, authorities from Israel.” The letter was signed by the university’s union of professors.

Following the vice-dean’s request, the local Jewish federation threatened to sue the university for racism. The resulting negative media attention prompted the dean to issue a public apology.

In the economic field, boycotters have had some success in Brazil by lobbying local governors and mayors to cancel deals with Israeli companies. For example, it succeeded in convincing the state government in Rio Grande do Sul to cancel a $17 million deal with Elbit and its Brazilian branch to build an aerospace camp in partnership with several universities. The governor of Rio Grande do Sul, Tarso Genro, belongs to the Workers’ Party and has Jewish ancestors, but has been quoted several times making critical remarks about Israel and is close to the Palestinian community living in southern Brazil.

The legendary Brazilian musician Caetano Veloso said that he would never return to Israel after participating in a tour of the West Bank with the NGO Breaking the Silence following his concert in Tel Aviv in 2015. Photo: Rodrigo Esper / flickr

The boycott movement is not enjoying unalloyed success in Brazil, however. In fact, commerce between Brazil and Israel has grown in recent years. From 2002-2015, trade between the two countries more than doubled, reaching $1.3 billion in 2014.

Nonetheless, due to the political positions of the Workers’ Party and its followers, as well as more radical left-wing movements, BDS will likely succeed in becoming a national trend. Only strong legislation against it, such as recent laws enacted in U.S. states, will prevent further damage.

At the moment, Israel’s image in Brazil is being defined by its enemies: A growing BDS movement and a prominent group of very influential academics, politicians, NGOs, and some of the media. The result is a pervasive narrative that denies the complexities of the conflict and propagates a simplistic view of evil Israelis and oppressed Palestinians.

However, events may be turning in Israel’s favor. President Rousseff was recently impeached and will stand trial in the Brazilian senate. For now, her powers have been stripped. As a result, a new acting government has taken power, and it is composed of people who are very friendly toward Israel, much more so than the last three Workers’ Party governments.

The current Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jose Serra, is a great friend of the Brazilian Jewish community and Israel, fostering collaboration with the Jewish state in many fields. Serra was Minister of Health during the 1990s and had strong ties to the Israeli pharmaceutical industry. In addition, an Israeli-born, Brazilian-raised economist, Ilan Goldfajn, was chosen as president of the Brazilian Central Bank.

But while these are positive developments for Israel, they have also created a backlash from the current political opposition, which is against Rousseff’s impeachment. Unfortunately, political beliefs in Brazil are often a zero-sum game. If Israel becomes associated with the right-wing parties, the Left feels it must reject it, regardless of the facts. A left- or right-wing voter adopts their party’s agenda wholesale. If this includes being against Israel, a voter will accept this without question. The challenge, then, is to convince left-wing parties to learn about Israeli affairs.

Efforts are underway to accomplish precisely this. In January 2016, a new initiative was created: The Israel Brazil Institute for Public Diplomacy (IBI). For the first time, a think-tank and educational institute will dedicate itself to defining Israel’s image in Brazil. It will coordinate, incentivize, educate, inform, and sensitize Jewish and non-Jewish Brazilians in regard to Israel. IBI is based on the belief that good information based on the facts will aid people in truly understanding the conflict in the Middle East.

View of Rio de Janeiro. Sugarloaf Mountain is on the right, and the “Christ the Redeemer” statue is on the left. Photo: Nati Shohat / Flash90

This is not just a political, but a moral obligation. Anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic forces must not be allowed to dominate any part of a society. The brainwashing and propaganda employed by Israel’s enemies are not simply manipulative and racist, but dangerous to democracy itself. Volunteers and professionals in public diplomacy must commit to the long-term work of communication and education with the clear objective that criticism and debate is welcomed, but delegitimization and demonization of Israel should be categorically rejected.

We must hope that in the near future Brazilian society will be friendlier and closer to Israel. At the end of the day, Israel represents democracy, diversity, freedom, and human rights; qualities that are important to Brazil and always will be.

Hopefully, Brazil will soon have more diplomats like Oswaldo Aranha who, under severe pressure, voted “yes” to the Jewish state, writing Brazil into the history books and playing an important role in the creation of the State of Israel.

![]()

Banner Photo: Nati Shohat / Flash90