It’s hard to remember a time when the Islamic Republic didn’t have U.S. citizens in its prisons. There’s a reason for that.

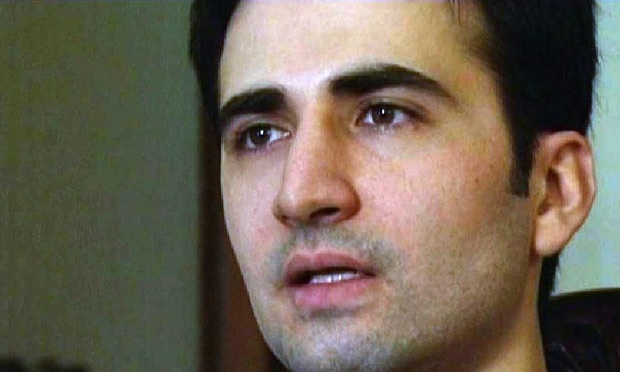

In April, American citizen and former Marine Amir Hekmati made a special plea to congressional leaders from Tehran’s notorious Evin prison, where he is incarcerated on trumped-up espionage charges. The United States, he said, needs to ensure that Iran faces “serious consequences” for its “serial hostage-taking,” before it claims another victim.

Hekmati was seized on his first trip to Iran. Born in Flagstaff, Arizona to parents who left Iran in 1979, Hekmati wanted to meet his extended family and visit his ailing grandmother. At the time, Iran was negotiating the release of American hikers Shane Bauer and Josh Fattal, who were taken in 2009. When then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad announced in September 2011 that the hikers would be released in a “humanitarian gesture,” the regime had already replaced that particular chess piece with Hekmati.

But few were aware of that.

Back in Michigan, all Hekmati’s family knew was that he was missing. He’d been in Iran for a couple of weeks and stayed a few nights with different relatives. On August 29, 2011, he called his mother to say that he’d be back home in a few days. That evening, family members ordered a taxi to his cousin’s apartment so he could attend a family dinner. He never took the cab. Concerned family members went to the apartment and found signs of forced entry and a scuffle. Amir was gone.

“We understood that he had been taken at that point,” his sister Sarah told me last year. “No police station was acknowledging then that they had him in their custody. We began to panic because we thought he was kidnapped.” Over the next four months, Amir was able to make one phone call to his family. He told them he was being held at Evin. But when relatives rushed to the prison, they were told there was no one there by that name.

Their nightmare was compounded when Hekmati surfaced on state TV that December. He was trumpeted as a captured American spy, and delivered an on-air “confession” the following month. It was quickly followed by a closed-door, half-day trial in which he was sentenced to death on a charge of conspiracy to commit espionage. “From January to March, imagine waking up every day to check the news to see if they’ve executed your brother,” Sarah said.

The death sentence would be reduced to a 10-year sentence on charges of collaborating with the U.S. government and “corrupting the Earth.” Amir’s appeals languish, rising and falling according to the mood of the Iranian judiciary. His family is trying to get attention from the media, the White House, the Iranian government, and Congress. They even lobbied other P5+1 governments at last year’s UN General Assembly.

In one heartbreaking message, Sarah Hekmati begged White House counterterrorism advisor Lisa Monaco to urge President Obama to mention her brother’s name in public. “Why when we make a request is it ignored?” she wrote. “Why am I forced to write this email to you AGAIN, the same subject AGAIN, the same plea AGAIN?” In July, after nearly four years, Obama finally said Amir’s name in a speech at the Veterans of Foreign Wars convention.

Whenever possible, Hekmati has lobbied on his own behalf, as well as for other Americans who are currently suffering at the hands of Iran and those who may be seized in the future. “While I am thankful that the State Department and the Obama administration have called for my release and that of my fellow Americans, there has been no serious response to this blatant and ongoing mistreatment of Americans by Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence, and they continue on with impunity,” he wrote in the letter to congressional leaders, dictated over the phone from prison.

As a war veteran who defended our nation in its time of need, I ask that you also work to defend my dignity and that of my fellow Americans by putting in place serious consequences for this serial hostage-taking and mistreatment of Americans by Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence for clearly illegal purposes. This has been going on far too long.

Unfortunately, Amir Hekmati is not alone in his ordeal. The Twitter hashtag #FreeAllFour, used to advocate for the release of all Americans held by Iran, also includes Jason Rezaian, Saeed Abedini, and Bob Levinson.

These men are linked by the fact that they are all in custody or missing, with no sign that they will be released. This was the case even as Iran and the P5+1 reached an agreement on Iran’s nuclear program. Many connected to these cases have stressed that they didn’t want the hostages released as part of the deal. This included Amir Hekmati himself, who fears concessions will only encourage more hostage-taking.

But Sarah Hekmati told me this past March that her family was “terrified” of the negotiations. If the parties came to a deal, “What incentive does Iran have any more to keep them, so why not release them?” she asked. But if a deal were signed, “They’ve received everything they’re asking for and there’s no motivation to release them, either.”

Ahmad Batebi landed in Evin Prison when he appeared in an iconic 1999 Economist cover photo holding a wounded student’s bloodied T-shirt aloft at Tehran student protests. He told me that Iran’s policy of taking hostages has its notorious roots in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Fifty-two Americans were held for 444 days after the sacking of the U.S. Embassy. Levinson, Hekmati, and Abedini have been held longer, and Rezaian will pass the 444-day mark in early October.

“We will have this behavior in the future. I cannot see a good future for human rights inside and outside Iran,” Batebi said. “Keeping these people in the prison is the Supreme Leader’s policy.”

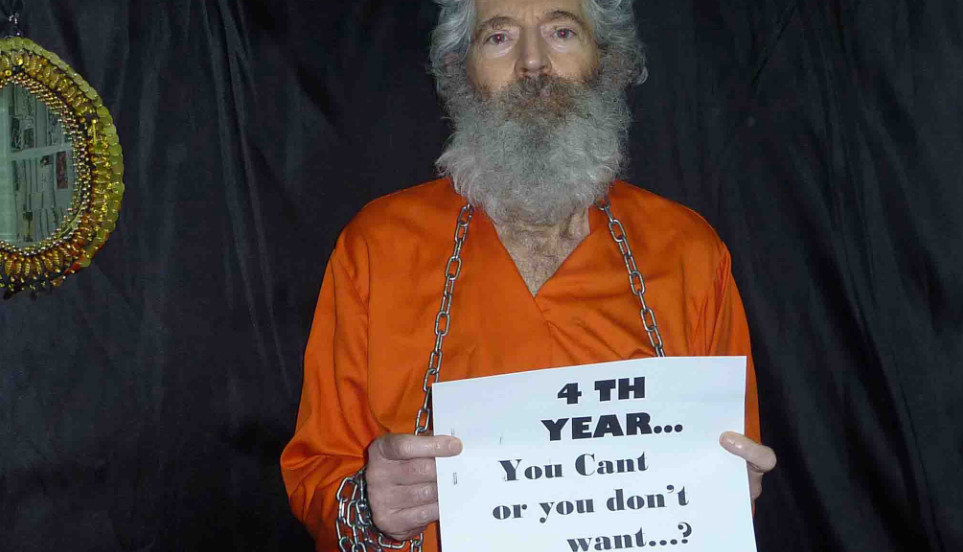

Bob Levinson was working as a private investigator on a case later admitted to be a CIA operation when he was taken by unknown kidnappers on March 9, 2007. The father of seven has become the longest-held U.S. hostage in history. With so much in question about his captors and current well-being, one can only look to his disappearance and a smattering of troubling communications for clues.

The family received a video of Levinson in late 2010. The next spring, they received photos showing him heavily bearded and clad in an orange jumpsuit. They’ve tried the White House petition site, the media, and more to try to draw attention to the case, for which the FBI is offering a $5 million reward. “We tried to contact you, but you never responded,” Bob’s son David said in a 2011 video plea to the kidnappers. “We need to know what you want our family to do so my father can come home safely.”

The Levinson video is a far cry from the slick productions terrorist organizations release today. It is a bleak, rough-cut video with the background noise of a TV or radio. “I have been held here for three and a half years,” Levinson says, sitting in a white shirt in front of an unadorned, distressed concrete wall. “I am not in very good health. I am running very quickly out of diabetes medicine. I have been treated well, but I need the help of the United States government to answer the requests of the group that has held me for three and a half years.”

“And please help me get home,” Levinson added, choking up. “Thirty-three years of service to the United States deserves something. Please help me.”

Since his capture, the congressional leadership in Levinson’s district has changed. The current congressman is Rep. Ted Deutch (D-Fla.), who is a leader in Congress’ unofficial tough-on-Iran caucus. When all four families appeared at an unprecedented House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing on June 2, Deutch addressed the standard administration answer that the State Department regularly raises the cases of the imprisoned Americans with the Iranians. “I appreciate ‘raising at every meeting,’ but the time has come to turn up the pressure,” he said. Levinson’s son Daniel told the committee that the family feared that “regardless of the outcome of the deal,” there might not be “a sense of urgency to get any of the loved ones home,” putting them “back to square one.”

Ali Alfoneh, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, told me that he believes Levinson has been held by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in a kidnapping the regime didn’t order, but has used to its advantage. “Whoever is in opposition is engaged in hostage-taking,” Alfoneh said.

The Ayatollah is not engaged in hostage-taking, not authorizing it. However, they tolerate it and, when it happens, use hostages opportunistically to extract and gain concessions from foreign governments whose citizens are held hostage by Iran. The head of state indirectly is involved.

In a 2012 interview with CBS, then-president Ahmadinejad all but admitted that the regime had a hand in Levinson’s kidnapping. “I remember that last year Iranian and American intelligence groups had a meeting, but I haven’t followed up on it,” he said when asked about the hostage. “I thought they’d come to some kind of an agreement.”

The Levinson family has received no evidence that he is alive since 2011.

Advocates for Saeed Abedini, a naturalized U.S. citizen born in Iran, maintain that he was imprisoned for his Christian faith. But the pastor was working on a project with the blessing and cooperation of the Iranian government when he was seized. This makes his ordeal even more senseless and heartbreaking to his family: He had permission to be there.

Abedini’s wife, Naghmeh, told me the tale in the summer of 2014: In 2000, the future pastor converted to Christianity in Iran and began founding churches in private homes with the knowledge and supervision of the Iranian government. Naghmeh had lived in America since her childhood, and met Saeed on a trip to Tehran in 2002. They wed in 2004, but Ahmadinejad’s stepped-up campaign against religious minorities forced them to return to the U.S. a year later.

Abedini was first arrested while establishing house churches on a 2009 visit to Iran. According to Naghmeh, this led to an arrangement with the Iranian government. Abedini wanted to help people, and “the intelligence police told him, why not do humanitarian efforts?” So he began building an orphanage in the Caspian Sea city of Rasht. From 2009-2012, Abedini made eight trips to Iran. The orphanage was close to opening. The board of directors was coming together. The neighborhood was eager to have the facilities.

On his ninth trip, Abedini was on a bus about to cross into Turkey. It was July 28, 2012. He was yanked off the bus by officials from the IRGC. They put him under house arrest with his parents. But two months later, the IRGC returned. They raided the home and dragged Abedini off to Evin prison.

Naghmeh was blindsided. She’d taken their two children to Iran near the end of 2011 and says they felt safe. She believes that surveillance of Abedini and his orphanage project was transferred from the intelligence police to the IRGC, which didn’t like what it saw. “We believe they used Saeed as an example to cause fear, to not want people to convert to Christianity,” she said. He is currently serving an eight-year sentence, but Naghmeh told the House committee in June that Abedini’s jailers tell him that he will “never come out” of prison unless he converts back to Islam. Saeed has been beaten and suffered internal bleeding. The American Center for Law & Justice has been representing Abedini as a victim of persecution against Christians. Notable advocates for human rights in Iran agree that his faith, not just his adopted nationality, led to his arrest and inhumane treatment.

Haleh Esfandiari of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars was arrested in 2007 on a visit to Iran—her home country—and held in solitary confinement from May to August of that year. “They don’t look favorably on converting out of Islam,” she told me in regard to Abedini’s case. “If you are lucky, you just keep a low profile and keep continuing your life. If you are unlucky, you’re like the pastor.” She added that “maybe appealing to the ayatollah as religious leader, not a political leader” could help bring Abedini home.

Ahmad Batebi believes that the Iranian regime is “scared” of the underground, tight-knit Christian communities in the country. Abedini, he says, gave them the perfect opportunity to “show this underground group that we can arrest you even if you go out of country.” He summarized the message to the Iranian people as “We can arrest you like we arrest these people. Better you be Muslim, because you are not safe.”

Demonstrating how Iran’s treatment of Americans responds to the news cycle, the day after Naghmeh Abedini’s latest testimony on Capitol Hill, the pastor was attacked by fellow inmates and given two black eyes.

In Amir Hekmati’s letter to Congress, he summed up the recent detention of The Washington Post’s longtime Iran correspondent, Jason Rezaian:

In the midst of negotiation with Iran over its nuclear program, as Secretary Kerry sits politely with the Iranians, shaking hands and offering large economic concessions to save them from economic meltdown, Jason Rezaian was added to the growing list of American captives, undoubtedly in hopes of milking more concessions from the U.S. government.

Rezaian was arrested in July 2014 along with his wife, Yeganeh Salehi, the Iran correspondent for the UAE newspaper The National. He had been reporting from Iran since 2008 and for the Post since 2012. Rezaian was held for months without charge. He was eventually accused of espionage on decidedly flimsy “evidence.” It included a U.S. visa application for his wife and an online interest form he filled out in 2008 for President Obama’s transition team.

“He said, ‘I’ve lived in Iran, I love Iran, I grew up in the United States, I love the United States, I want our countries to be more harmonious. How can I help you guys out? Is there anything I can do in the upcoming administration?’ That’s basically the extent of that letter,” Rezaian’s brother Ali told Bloomberg News, adding, “It wasn’t officially an application for a job.”

Ali says that his brother has been “subjected to months of interrogation, isolation, and threats” in Evin prison, as well as “deprived of basic medical treatment exacerbating minor medical issues and risking permanent physical harm.”

Rezaian’s closed-door trial began at the end of May—between the fourth and fifth rounds of nuclear negotiations in Vienna. Michael Rubin, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, told me,

Whether or not he was taken to subvert the negotiations, the timing of his court dates certainly suggests that the Iranian government was trying to undercut subsequent talks and must have been in a state of disbelief when Americans didn’t take the hint and ignored the fate of an Iranian-American.

Haleh Esfandiari believes Rezaian was a victim of the Intelligence Ministry, which was trying to embarrass the Iranian president at a critical time. “Sure, they knew that they cannot derail nuclear talks, but wanted to embarrass Zarif and Rouhani,” she said of Foreign Minister Javad Zarif and President Hassan Rouhani.

“If they have a hostage, they can put pressure on the West on nuclear negotiations—that’s the first goal,” said Ahmad Batebi. The regime’s second goal, he believes, is to put the Iranian people on guard about the supposedly pervasive threat from the West.

They need to show to people and prove to people we have a bad situation, saying to people, “We have to be careful at all times, we have to watch everything all times, the enemy is trying to find out information about us, about our activities—they send spies for us, so we have to be careful.

The administration’s response to Rezaian’s arrest has been minimal. In mid-July 2015, while pitching the nuclear deal with Iran, Secretary of State John Kerry simply said, “We are working very hard on him.” His family members likely found this less than comforting.

When Rep. Dan Kildee (D-Mich.) entered the House of Representatives in 2013, his constituent Amir Hekmati had already been behind bars for more than a year and a half. Kildee has since become a key advocate in the House for all four hostages held by Iran. In June, he introduced a resolution that led to a unanimous vote demanding their immediate release. When the hostages’ families testified before the Foreign Affairs Committee, Kildee stressed that Iran is “holding innocent Americans guilty of nothing but being American.” He says not a day goes by that a colleague doesn’t ask him about Hekmati and the other Americans held in Iran.

When I asked him why Iran seized Hekmati, Kildee replied,

I can’t speculate on Iran’s reasoning, but clearly Amir is an innocent American citizen that needs to be released. If Iran wants to rejoin the global community, they can’t continue to take and hold political prisoners like Amir. We are trying to move in a more positive direction with Iran and clearly their continued imprisonment of American prisoners makes that more difficult.

Kildee echoed the frustration of other House members and senators who represent the hostages, as well as the frustration of their families. “The onus is really on Iran to do what is right,” he said.

The Iranian government has it fully within their authority to make this decision to release Amir and the other Americans they hold. For Amir Hekmati, all he did was volunteer to serve in the military in the United States, his home country and place of his birth, and then went to visit family in Iran for the first time.

Hekmati did indeed serve honorably as a sergeant in the Marine Corps during the Iraq war. After leaving the military, he put his linguistic skills to work as a contractor. His sister Sarah says he was open about his service when applying for a visa. Iranian officials told him it wouldn’t be a problem.

Ahmad Batebi believes Iran may have thought it could obtain sensitive information from the veteran. “They need some confidential information about structure in the U.S. military. They think they can find some information from him. That was the first reason,” he says. “Second, the Iranian government puts pressure on the West for Iranian citizens in prison. They are trying to put pressure on the U.S. government to release these people in the United States.”

Indeed, Hekmati has said as much himself. In a 2013 letter to Secretary Kerry, he asserted that his captivity “is part of a propaganda and hostage-taking effort by Iranian intelligence to secure the release of Iranians abroad being held on security-related charges.” He said intelligence officials had told him they were trying to swap him for two Iranian prisoners. Nonetheless, he wrote Kerry, “I had nothing to do with their arrest, committed no crime, and see no reason why the U.S. Government should entertain such a ridiculous proposition.”

Esfandiari echoed Batebi and Hekmati’s suspicions. She says officials told her the same thing: They were hoping to swap her for Iranians held by the United States.

One Iranian official all but confirmed this theory. On May 28, Iranian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Marziyeh Afkham accused the United States of “projection” when it demanded the return of hostages. “They should take a look at the unfair prosecution of Iranian citizens who are jailed in the U.S. on baseless charges,” she said.

Michael Rubin theorizes that Hekmati “may have been a chip for which to trade. Once they realized that the U.S. wasn’t going to make an issue of him, rather than release him they thought ‘what the hell, we lose nothing by keeping him.’”

Risibly, Iran claims that the U.S. doesn’t have jurisdiction over Hekmati and Rezaian, even though they were born and bred in the United States. This bears repeating: According to Iran, the U.S. has no jurisdiction over its own citizens. Indeed, the Iranian government did not recognize the American citizenship of Roxana Saberi, a journalist arrested in 2009 and held in Evin prison on espionage charges for 101 days. Saberi was born in New Jersey to an Iranian mother and a Japanese father.

As far as Hekmati is concerned, Iran can keep his citizenship. “Considering how little value the Ministry of Intelligence places on my Iranian citizenship and passport, I, too, place little value on them and inform you, effective immediately, that I formally renounce my Iranian citizenship and passport,” he wrote in a letter to the Iranian Interests Section in Washington this spring. “My Iranian heritage and affinity for the Iranian people will always be a part of me, but I wish to have no ties to an organization that places so little value on my human rights and dignity and is willing to destroy an entire family for simple propaganda purposes.” Shockingly, the State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2014 refused to recognize Hekmati’s renunciation, referring to him as “a dual citizen held in Evin Prison since 2011.”

Esfandiari used Iran’s refusal to recognize dual citizenship against her captors. “When I was in jail, they told me four Iranians were held by Americans in Iraq. They told me there is always the possibility of a swap,” she said. “I told them, ‘You tell me I’m an Iranian, so you want to swap an Iranian for Iranians?’ And that put an end to that.”

The larger question is: Why does the regime fear Americans of Iranian heritage? Michael Rubin believes that it is because Americans bring with them a “vibrancy of culture without Islamic Revolution,” which is a “threat to the regime.”

“When the revolution comes,” he said, “it’s going to be led by an Iranian.”

Iran opportunistically seizes American targets who may or may not be of value at a particular point in time. It hopes to use them as a bargaining chip or to send a message. If necessary, they can be saved for a moment when Tehran wants extra diplomatic leverage.

These are time-honored tactics. “There’s absolutely nothing new about hostage-taking in Iran,” Ali Alfoneh said.

It’s a perfectly normal procedure and political practice in the Islamic Republic. That has been the case since the first day of the revolution and continues until today. Usually, the legal government is opposed to hostage-taking as it will be facing the protests of foreign governments. At the same time, the opposition is always actively engaged in hostage-taking. It serves their interest to show the government as weak.

Ahmad Batebi believes that the biggest obstacle to the release of American hostages is that the real culprits are the IRGC and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. “The real government is that one, the government in the shadow,” he says. “The taking of Americans is approved by Khamenei. All details are sent to the Supreme Leader. He would send back details of what they should do. The Hassan Rouhani government is a puppet.”

The unwillingness of the American government to stand up on behalf of the hostages is also a major problem. Michael Rubin echoes what many lawmakers have been saying: The administration “forfeited our leverage” on the hostages during the nuclear talks. “I can’t think of a time in another administration—Democratic or Republican—that has been so indifferent to the taking of American hostages,” he said. “What we should have been saying is, ‘We are not going to come to the table, we are not going to come into the same room with you if you’re holding American hostages.’ Now we have inflated the cost of the hostages by giving $100 billion for nothing. Iran isn’t into goodwill.”

And Iran gets away with it, in part, thanks to relatively low interest among the American public. People are not displaying yellow ribbons en masse as they did during the Iran hostage crisis. Many updates go unnoticed by the media and the hostages’ families battle the perpetual peaks and valleys of public awareness campaigns.

“Maximum press coverage usually sees a release of those individuals. Pressure on the Iranian government increases so much,” Alfoneh says. But without this kind of coverage, American hostages “end up rotting in prison for years and years.”

American government policy is not helping the situation. Indeed, Naghmeh Abedini was told by the State Department—which did not issue a statement on the issue until almost six months after her husband was taken into custody—to wait and see how things developed. This is typical. And as the U.S. dithers, the hostages’ families are being run ragged by years of campaigning for their loved ones, knowing they can’t sit and wait.

Representative Kildee holds out hope that Iran can be pressured to do the right thing.

Iran would be viewed much more favorably if it returned Amir and the other prisoners to their families. I think Iran needs to understand that the world will continue to view them through a more skeptical lens if they continue to arrest and hold innocent Americans like Amir as political prisoners. If they want to be taken seriously, they have to release the Americans that they hold.

![]()

Banner Photo: Washington Post