In an analysis published in Tablet, Lee Smith comments on a recent New York Times report concerning the influence of foreign money on think tanks to evaluate how Qatar’s support of the Brookings Institution might have affected Martin Indyk, the head of its Foreign Policy Program. In between stints at Brookings, Indyk was appointed by Secretary of State John Kerry to shepherd the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations from July 2013 to April 2014. Smith argues that the New York Times, in covering the broader question of foreign influence over Washington think tanks, oddly underplayed the Qatar-Indyk link:

But far from trumpeting its big scoop, the Times seems to have missed it entirely, even allowing Indyk to opine that the best way for foreign governments to shape policy is “scholarly, independent research, based on objective criteria.” Really? It is pretty hard to imagine what the words “independent” and “objective” mean coming from a man who while going from Brookings to public service and back to Brookings again pocketed $14.8 million in Qatari cash. At least the Times might have asked Indyk a few follow-up questions, like: Did he cash the check from Qatar before signing on to lead the peace negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians? Did the check clear while he was in Jerusalem, or Ramallah? Or did the Qatari money land in the Brookings account only after Indyk gave interviews and speeches blaming the Israelis for his failure? We’ll never know now. But whichever way it happened looks pretty awful.

According to Smith, taking Qatari money for his institution may have compromised Indyk’s credibility with both Israel and the Palestinians.

Certainly Jerusalem has good reason to be wary of an American diplomat who is also, or intermittently, a highly paid employee of Qatar’s ruling family. Among other things, Qatar hosts Hamas’ political chief Khaled Meshaal, the man calling the shots in Hamas’ war against the Jewish state. Moreover, Doha is currently Hamas’ chief financial backer—which means that while Qatar isn’t itself launching missiles on Israeli towns, Hamas wouldn’t be able to do so without Qatari cash.

Of course, Hamas, which Qatar proudly sponsors, is a problem not just for Israel but also the Palestinian Authority. Which means that both sides in the negotiations that Indyk was supposed to oversee had good reason to distrust an American envoy who worked for the sponsor of their mutual enemy. In retrospect, it’s pretty hard to see how either side could have trusted Indyk at all—or why the administration imagined he would make a good go-between in the first place.

The connection between Qatar and Indyk prompts Smith to ask, “why in the midst of Operation Protective Edge this summer did Kerry seek to broker a Qatari- (and Turkish-) sponsored truce that would necessarily come at the expense of U.S. allies, Israel, and the PA, as well as Egypt, while benefiting Hamas, Qatar, and Turkey?” When Indyk stepped down from his position at the State Department, Reuters reported that he would continue to consult with Kerry.

In Qatar’s Rise and America’s Tortured Foreign Policy, which was published in the August 2014 issue of The Tower Magazine, Jonathan Spyer criticized Kerry’s insistence on involving Qatar in the ceasefire talks, noting:

This move, fronted by John Kerry, was especially ironic, given his personal record on the fundamental contradiction posed by Qatar and its support for terrorism. It was Kerry himself, speaking at the Brookings Institution in March 2009, shortly after the last defensive war Israel waged against Hamas, who warned that “Qatar cannot continue to be an American ally on Monday that sends money to Hamas on Tuesday.”

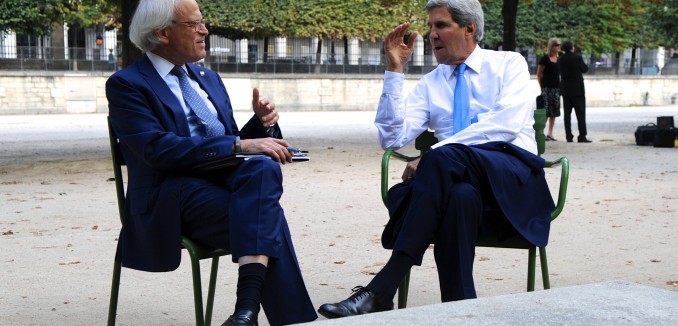

[Photo: Wikimedia]