Theodor Herzl’s original vision for Zionism included Jews, Christians, and Muslims living in harmony with a shared purpose. The history of Zionism tells us that this moment may not be too far off.

One would be hard-pressed to find an allegation that has not been leveled at the Jewish people’s movement for self-determination in their homeland: Zionism is racism. Zionism is colonialism. Zionism is apartheid. No social evil has been missing from the placards raised at anti-Israel and anti-Zionist demonstrations, all claiming “Zionism = X.”

These allegations have been exposed time and again as libels and smears, but even the greatest defenders of Zionism have failed to notice a much more positive, and indeed remarkable, facet of this century-old ideology: Zionism = Inclusion.

That is to say, Zionism was, is, and will likely continue to be on a steady trajectory of increasing inclusiveness. Contrary to those who say Zionism is an exclusivist ideology, from the moment of its foundation, it was one of the world’s most inclusive national and political movements.

This is not to argue that the Zionist inclusiveness has been one of singing “Kumbaya” with open arms. Zionism became inclusive because it was necessary for its survival. Its inclusiveness was, originally, largely due to pragmatic considerations. Only later did it become inherent in the ideology itself. Without inclusiveness, Zionism would have died in infancy.

In its early years, Zionism was a marginal and radical movement among the Jewish people. In 19th century Europe, Jews mostly responded to the hostility of their host countries by attempting to assimilate into European society or immigrating to the United States. Few considered the restoration of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel as a serious alternative. Many even viewed it as a threat to their efforts at assimilation. So from its very beginnings, Zionism could not afford to exclude anyone. If it were to survive, anyone willing to rally to its flag would be welcome.

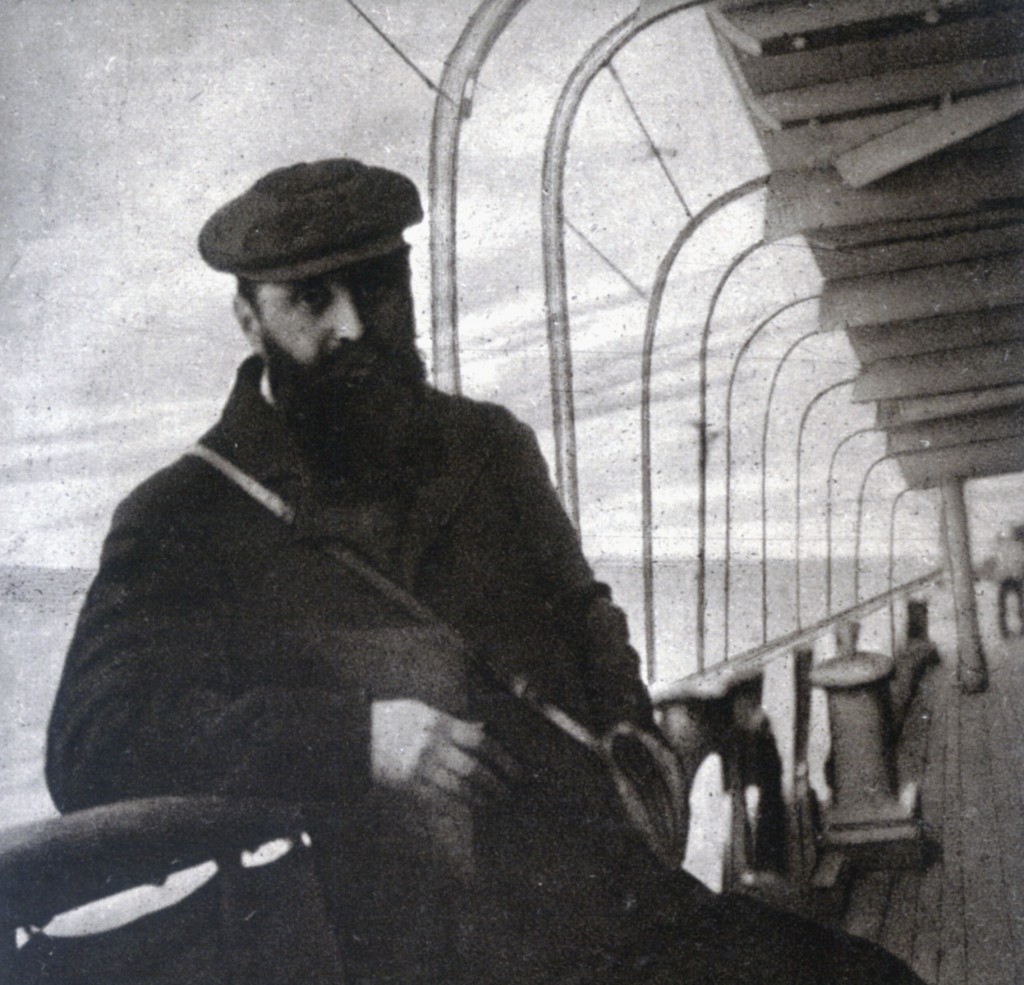

The realization that inclusiveness was critical to Zionism’s survival dawned on its founder, the writer and dramatist Theodor Herzl, as he sought support for his ideas among the Jews of Europe. Herzl’s initial vision for a renewed Jewish state was a kind of Vienna in the Levant, a Central European utopia on the banks of the River Jordan. The intended audience for his vision was Jews such as himself—cultured, assimilated, and European—who would create a better Europe in the Middle East. A Europe that, unlike the real one, would be a place where Jews could feel safe, hold any position in society, and never need to question their sense of belonging.

It was to these Jews that Herzl turned when he wrote his manifesto, The Jewish State. He appealed to them in Britain, France, Germany, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But after repeated attempts, he was dismayed to find they were not interested. Worse still, they rejected his ideas by asserting that they were solely British, French, German, or Austro-Hungarian. As the writer Amos Elon noted, the response to Herzl in Vienna was, “We Jews have waited two thousand years for the Jewish state and it had to happen to me?”

Like most Jews of Central and Western Europe, who saw themselves as modern and enlightened, Herzl despised the Jews of the East. In his eyes, they were primitives stuck in medieval times, resistant to the Enlightenment and decidedly un-European. He certainly did not think they could carry the mantle of Zionism and build the state he envisioned. The last thing he wanted for a Jewish state was to replicate the shtetl life of Eastern Europe and Tsarist Russia. But even as Herzl was being rebuffed by the cultured Jews of the West, he was, as Elon wrote, “surprised by the resonance of his tract in the East; he had expected it to strike hardest in the assimilated West, not in the East, which he regarded as backward, even primitive.” But the Eastern European Jews were the ones who embraced Zionism. They were inspired by his vision. They wanted to be the builders of the new state. And they were willing to do what it took to resurrect Jewish sovereignty in the blistering heat of the Land of Israel.

Touring Europe with his vision, whether among the shtetl immigrants of London or the Jews of Bulgaria, Herzl was overwhelmed by the reception.

News of his passage had preceded him. When the train stopped at the station an enormous crowd of Bulgarian Jews hailed the author of The Jewish State as their long-awaited savior…. People rushed to kiss his hand, and in the synagogue he was placed by the altar. He did not know how to face the crown without turning his back to the holy Torah. But a man called out: “It is all right for you to turn your back to the altar. You are holier than the Torah….” With his magnificent beard, his glowing eyes, his proud frame, and fine, simple gestures, Herzl stood on the stage, looking “as kings wish to look but seldom do.”

He was received by the Jews of the East like the Messiah who would take them back to the land of their ancestors.

Overwhelmed by this reception, Herzl the writer realized that the time had come for rewriting. He recast the Jews of Eastern Europe as the true national Jews. He wrote them into his story as those who had kept their sense of being a nation while the assimilated Jews of the West had not. In Herzl’s rewritten narrative, the Jews of Eastern Europe became better suited to the task of building a Jewish state than anyone else; because they, above all others, knew what it meant to be a nation; and Zionism was first and foremost about the national revival of the Jewish people.

During the first Zionist Congress, Elon writes,

The Russian Jews had left the deepest impact [on Herzl]. Warm hearted, soulful, eminently practical, deeply steeped in folk tradition, which in the East was still very much alive, they had none of the identity problems of the Western Jews, none of his sense of alienation. Herzl had previously thought of them as poor, oppressed candidates for relief, living in a “primitive” East; it took the congress to open his eyes: “How ashamed we felt, we who had thought that we were superior to them. Even more impressive was that they possess an inner integrity that most European Jews have lost. They feel like national Jews but without narrow and intolerant conceit…. I had often been told in the beginning, ‘The only Jews you’ll win will be the Russian Jews.’ Today I say, ‘They would be enough!’”

Indeed, over the next three decades, the Jews of Eastern Europe became the primary adherents of the Zionist vision and the ones who built its foundations against overwhelming odds. By embracing them and rewriting his narrative to reflect their enthusiasm for the cause, Herzl demonstrated that, for Zionism to survive, it would need to include everyone who supported it. He also showed how to achieve this: By rewriting the story to include the previously excluded group; and to do so in a way that not only included the new group, but made it one and the same with the Zionist vision.

Inclusiveness has many forms, and different countries and ideologies have found different ways of accomplishing it. France has a secular republican model under which anyone can become French if they adopt the values of the republic, live in a secular public sphere, keep competing identities such as religion to the private sphere, and embrace French culture and language. America has a post-national model that depends heavily on embracing the principles of the constitution and the “American way of life.” Britain has a post-colonial model under which peoples and religions are united under the scepter of the queen. All models of inclusion in countries that claim to be inclusive are problematic. All of them are partial. All suffer from a gap between the claim to inclusion and the reality. And all are challenged by groups who do not accept the “rules for inclusion.” In that sense, Zionist inclusiveness is no different. But its mechanism is.

The Zionist mechanism is one of retelling and rewriting its story as if Zionism was always designed to include a previously excluded group. This mechanism is not one of simple assimilation, “multiculturalism,” or even the “melting pot.” It is a constant rewriting of the story of Zionism so that a new story emerges to erase the old, thus creating the sense that Zionism has always been able to include the previously excluded group.

This is no different from the way all human beings adapt to changing circumstances. We write and rewrite our histories. We take moments of failure, despair, and rejection, and remake them into stories of growth, transformation, and triumph. We create a unified narrative that makes sense out of everything that has happened to us. We tell ourselves it had to happen so we could become who we are today. Internally, almost all humans—except for the clinically depressed—are like Pangloss, the perennially optimistic philosopher in Voltaire’s Candide.

The Zionist mechanism works in the same manner. It is a constantly retold story, but at any given moment it is also a unified one. It is not a legalistic mechanism of “neutral” citizenship in a “neutral” state, where abiding by the law is the only requirement and all who abide by the law are equally included. The Zionist state believes in equality before the law, but Zionist inclusiveness works in a very different way: Zionist inclusiveness is about the story, not the law.

One of the most remarkable examples of Zionism’s ability to rewrite its story and transform its narrative is its relationship to the Holocaust. This narrative transformation has been achieved so completely that almost everyone now believes the State of Israel was born as a direct result of the Holocaust, and owes its existence to the tragedy and its survivors. To understand the magnitude of this transformation, we need to appreciate how difficult it was for Zionism to deal with the Holocaust.

Zionism was first and foremost an ideology of activism. It was a rebellion against Jewish passivity in exile, a rejection of the Jews’ resigned attitude toward their fate as a persecuted and marginalized minority. As a secular movement, it rebelled against simply waiting for the Messiah. It called for the Jewish people to be their own Messiah, to go by themselves to the Holy Land to restore Jewish sovereignty, rather than waiting for God’s anointed to do it for them.

In addition, Zionism contained an element that called for the total negation of Jewish life in exile. This, however, was not true for all Zionist thinkers. Herzl, for example, imagined that the re-establishment of Jewish sovereignty would also contribute to the life of Jews in exile by relieving them from the status of a stateless people at the mercy of the nations. He described in his novel Altneuland (“Old-New Land”) that with the establishment of the Jewish state, “Jews who wished to assimilate with other peoples now felt free to do so openly, without cowardice or deception. There were also some who wished to adopt the majority religion, and these could now do so without being suspected of snobbery or careerism, for it was no longer to one’s advantage to abandon Judaism.”

Herzl thought that Jews would be able to walk proudly as equals among the nations once they had a state, even if they did not become its citizens. But as the situation in the Diaspora became more severe and ultimately genocidal, the choice made by many Jews to remain in Europe was scorned. For many Zionists, the growing strength of their embryonic state and the growing danger faced by the Jews of Europe delegitimized life in the Diaspora.

The negation of the exile (shlilat ha’galut in Hebrew), as it became known, was not just about negating the legitimacy of Jewish life in the Diaspora, but also negating its very essence. Zionism created an entire series of opposites expressing this: Active vs. passive, strong vs. weak, proud vs. humiliated, self-sufficient vs. dependent, healthy vs. sick. Zionism came to be seen as a cure for the sickness inflicted upon Judaism by the exile.

Zionism adapts by rewriting the story to include the previously excluded group, doing so in a way that not only includes the new group, but makes it one and the same with the Zionist vision.

So when the Holocaust occurred, it was an affront to Zionism’s core ideology. The Jews who perished in the Holocaust represented everything that Zionism wanted to change. The victims were seen as passive, going to their deaths like “lambs to the slaughter.” They were weak, dependent, and suffered the greatest possible humiliation—an industrial genocide. Whenever they rebelled, it was because they were Zionists. The Warsaw Ghetto resistance fighters, for example, became national heroes, in part because they were members of Zionist youth movements preparing to immigrate to Israel. The survivors were even worse in the Zionist perception. They were suspect simply because they had survived. The suspicion was that they must have engaged in deceitful and treacherous actions in order to do so.

The nascent State of Israel took the Holocaust survivors in and recruited them to fight for its independence. This was, again, a pragmatic inclusiveness. Israel needed them to survive. But it did not want to hear their story, and it found no place for them in the Zionist narrative. At best, they served as Exhibit A of why there could be no Jewish life in exile. They were the negative to Zionism’s positive.

Beginning with the public trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961, however, the people of Israel not only started to listen to the survivors, but to rewrite the story of Israel and Zionism accordingly. It did not happen quickly, but over the next few decades, the story of the Holocaust and its survivors became so integrated into the story of Zionism that many today believe the Holocaust is the reason for Israel’s existence. This has become such a dominant story that many people around the world—including Jews and Israelis—are barely aware of the history of Zionism and the pre-state Zionist community that preceded the Holocaust.

The survivors of the Holocaust eventually became Israel’s new heroes. Not just the Zionist resistance fighters, but any and all who survived. Just this past Holocaust Remembrance Day, Twitter and Facebook were taken over by photos of soldiers with Holocaust survivors, who were hailed as Israel’s true heroes.

The retelling of Zionist history to incorporate the Holocaust and its survivors is now complete. Zionism genuinely stripped itself of its scornful attitude toward the survivors, and achieved complete inclusiveness by transforming its narrative.

A new immigrant family moves into a ma’abara, a refugee absorption center, near Tel Aviv. Photo: Zoltan Kluger / flickr

Another major group is still in the process of undergoing narrative inclusion: The Jews who immigrated to Israel from Arab countries. Prior to the Holocaust, they were a tiny minority of the Jewish world. Only one million out of a world total of 18 million Jews resided in North Africa and the Arab Middle East. With colonialism ending and the impending establishment of the State of Israel, tensions between the Muslim Arab population and the Jews rose. Over the course of only a few years, these Jewish communities—which in most cases predated Islam—were removed. A large number of the Jews fleeing these countries found refuge in the newly created State of Israel.

Much like survivors of the Holocaust, the Jews from Arab countries were recruited into the Zionist state-building effort, but they were not welcomed or included in any real sense. They were viewed as being “not us”—“nicht unsere” to use the Yiddish term. For decades, they suffered overt and covert discrimination. But they slowly found themselves, mostly through their own struggle and effort, becoming part of Israeli society, to the point that they all but became Israeli society. To a great degree, this inclusion was achieved through marriage. When I speak to large groups of Israeli students or soldiers I like to conduct a little exercise. I ask how many among them have four grandparents of the same ethnic origin. Usually, in a room of 200, less than ten hands will be raised.

Many will no doubt claim that, with all due respect to the achievements of Zionism, it has never sought or succeeded in including non-Jews. It is one thing to include all the Jews in the world—an impressive feat in itself—but quite another to include non-Jews.

First, it is important to note that Herzl’s own conception of Judaism was so secular and national that he felt religious Muslims, Christians, and Jews could all be Zionists. He thought the Jewish state should be akin to the French state, allowing people to have different religious faiths or none at all. So, at least as conceived by Herzl, Zionism was not meant for the Jews alone, and non-Jews could partake in it. Throughout Altneuland, Herzl emphasized, “The fundamental principles of humanitarianism are generally accepted among us. As far as religion goes, you will find Christian, Mohammedan, Buddhist, and Brahmin houses of worship near our own synagogues.” In his vision of a future Jewish state, “Religion had been excluded from public affairs once and for all. The New Society did not care whether a man sought the eternal verities in a temple, a church, or a mosque, in an art museum or at a philharmonic concert.” Herzl’s ideal as stated in Altneuland is “We do not ask to what race or religion a man belongs. If he is a man, that is enough for us.” In the novel, in fact, it is exclusionary Jews who are portrayed as the main enemy.

Many Soviet immigrants to Israel are an example of Herzl’s idea in action. Though they could claim citizenship due to their Jewish ancestry, many were not Jews themselves, and some were practicing Christians. Yet their immigration to Israel was considered highly valuable—even one that “saved” the country. In fact, when their status as non-Jews did became an issue—such as burial of fallen soldiers—it was met with anger from the broader Israeli society; indicating that, for most Israelis, they belonged fully and unquestionably.

The Herev (sword) Battalion, composed completely of Druze citizens who choose to enlist in the unit, conducts a training exercise. Photo: Matanya / Wikimedia

Over recent decades, Israel has also sought to include its Druze and Bedouin communities. The initial reason was, again, pragmatic. In this case, the need for soldiers. As early as Israel’s War of Independence, many Bedouin and the entire Druze community joined the Jews in fighting off the invading Arab armies. From that moment, the Druze and many Bedouin were included in the Israel Defense Forces. Since then, Druze and Bedouin military heroes have been hailed by Israeli society and media. Indeed, during the latest conflict with Hamas, a Druze senior commander became a media hero after he demanded to be sent back into the field despite severe injuries. Many Druze self-identify as not merely Israelis, but also Zionists. This is not to say that there are no problems with discrimination or other issues, but it does show that Zionism is willing to embrace those who align themselves with it, whether Jewish or non-Jewish. Indeed, it seems that Zionism only finds it difficult to include non-Jews when they embrace competing Arab or Palestinian national identities. Zionism in itself can include non-Jews in its story, so long as they do not align themselves with a hostile narrative.

The current frontier of inclusion is that of ultra-Orthodox Jews and Israeli Christians.

In the past, Israeli Christians by and large adopted Arab and Palestinian identities. Christians were among the most important thinkers and shapers of modern Arab and Palestinian nationalism, and often its most zealous adherents. This is due, in part, to their status as a minority among Arab Muslims. In recent years, however, as the Arab Spring revolutions have placed the lives of Middle Eastern Christians in jeopardy, Israeli Christians have begun to explore the possibility of an Israeli rather than Arab Christian identity. As Arab identity is increasingly perceived as exclusively Muslim and even openly hostile to Christians, Israeli identity has emerged as a new possibility for identification. Like the Druze and Bedouin, this is being explored through service in the IDF, as more and more voices in the Christian community look to military service as a means of engaging with “their state.” In response, the IDF is taking steps to make military service more accessible. This process has only just begun and is politically controversial, but it demonstrates again that Zionism is willing and capable of integrating non-Jews who do not embrace a competing identity hostile to Zionism.

Ultra-Orthodox Jews, for their part, have had an ambivalent relationship with Zionism from the beginning. Zionism was a thoroughly modern movement that believed human beings should shape their own fate, rather than passively accept the will of God. In addition, it was composed of mostly secular and even atheist Jews who rebelled against the religious way of life. As a result, many ultra-Orthodox thinkers saw Zionism as heresy. Some extreme ultra-Orthodox sects even claimed that Zionism was an affront to God and an obstacle to the realization of God’s plans for the Jewish people, so only by destroying the State of Israel can the arc of history be put right again.

Father Gabriel Naddaf of Nazareth, an Arab-Israeli Greek Orthodox priest, has issued a call to Arab Christians to serve in the IDF and integrate into Israeli society. Photo: ShalomYerushalayim1 / YouTube

Yet the Holocaust left the surviving ultra-Orthodox Jews in need of refuge, and many found it in the State of Israel. Nonetheless, even ultra-Orthodox Israelis have found it difficult to come to terms with the existence of a secular Jewish state, and especially with its success. Moreover, unlike Zionists who believed that sovereignty was essential to Jewish survival and prosperity, the ultra-Orthodox felt that the exile posed no threat to the future of the Jewish people, and might even be preferable.

For most of Israel’s existence, the Zionist majority was willing to let the ultra-Orthodox maintain their way of life and remain on the margins of Israeli society. But in recent years, as the ultra-Orthodox community has become much larger, more and more Israelis feel that the status quo cannot be sustained. In particular, they believe ultra-Orthodox Jews’ heavy dependence on the welfare state, low participation in the labor force, and almost non-existent military service places an unfair burden on other Israelis.

So began the battle to include ultra-Orthodoxy in the Zionist narrative. Initially, it took the form of a demand for military service and greater participation in the labor force. In other words, the motivation was once again pragmatic. Zionism wants the ultra-Orthodox to be taxpayers and soldiers. But over time, it is likely that the mechanism of narrative transformation will begin to operate. The Zionist story will be rewritten so as to make ultra-Orthodoxy into another, equally genuine form of Zionism. The 2,000-year-long continuing existence of ultra-Orthodox communities in the holy cities of Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias, for example, may be portrayed as having paved the way for modern Zionism and secured the path for the return of the Jewish people to their homeland.

The last frontier of inclusion is unquestionably that of Israel’s Muslims, who currently describe themselves as Arab Palestinian Muslims holding Israeli citizenship, and it is the most difficult. At the moment, it seems almost ludicrous to think about their future inclusion in the Zionist narrative. Israeli Muslims themselves are likely to see the idea as an affront to them and their sense of Arab-Palestinian national identity. But I would like to present the possibility that, sometime in the future, such inclusion could take place.

Currently, the Palestinian national movement and Zionism appear so at odds that it is nearly impossible to conceive of a situation in which the Zionist narrative could be sufficiently rewritten to include Israeli Muslims. The furthest that most Israeli Muslims are willing to go in this direction is to demand a “neutral” Israeli state, stripped of any signs or symbols of being Jewish or Zionist. The argument put forth by them and especially their leadership is that as long as the state of Israel continues to be Jewish or Zionist, Muslims can have legal rights, but will never truly be a part of Israeli society.

As a result, for many Israeli Muslims, the only path to full inclusion and belonging is an end to Zionism. In the current situation, this is somewhat understandable. If Zionism and Palestinian nationalism are in direct conflict, the embrace of one naturally implies the rejection of the other. But it is also, of course, impossible for Zionism to accept, since it demands not the rewriting of the Zionist story, but the burning of the book itself.

As a result, the inclusion of Israeli Muslims in the Zionist narrative is likely to happen under one of two extreme conditions: Full peace between Israel and the Arab world, or an Arab world so engulfed in chaos and brutality that Israeli Muslims distance themselves from an Arab Palestinian national identity in search of an alternative. Under one of these extreme but not impossible scenarios, Israeli Muslims would no longer be Arab Palestinian nationalists, but Israelis and Zionists.

The next frontier of Zionist inclusion is adapting the story to fit Christians, ultra-Orthodox Jews, and possibly Muslims.

Should either of these scenarios materialize, the obstacles to inclusion would be lifted, at least in principle. One could begin to imagine the Zionist narrative being retold so that Israeli Muslims are fully included in the story. This inclusive narrative could be about how Muslims tended and kept the land for centuries, welcoming the returning Jews to share it for the good of all. It could be the story of how local traditions of generous hospitality led the local Muslims to provide refuge to the Jews coming to their shores. It could be a story with new heroes—Jews and Muslims who exemplified cooperation long before it was the norm; Muslims who protected Jews from harm; Muslims who sold land to the Jews and shared valuable agricultural knowledge with them; and Muslim teachers who taught about Zionism without neglecting their own side of the story.

It could be a narrative that resurrects the buried history of Muslim support for Zionism in Palestine. This history was recently uncovered in Hillel Cohen’s book Army of Shadows: Palestinian Collaboration with Zionism, which covers the many dissident elements in the Palestine Arab Muslim community that viewed Zionism positively—as Herzl had hoped—and even assisted it through land sales, intelligence, and military assistance against the British. It could be a story that reminds us of heroes like Haifa mayor Hassan Bey Shukri, who wrote to the British government in 1921,

We strongly protest against the attitude of the said delegation concerning the Zionist question. We do not consider the Jewish people as an enemy whose wish is to crush us. On the contrary, we consider the Jews as a brotherly people sharing our joys and troubles and helping us in the construction of our common country.

It could perhaps become the story of how the Muslims, together with Jews, made the land of Israel whole again, bringing together all the religions that originated and flourished within its borders. It could be a story of return and reunification. A story of how the Muslims had to come to terms with being a minority and the Jews with being a majority before both could truly live as one, introducing the key element in any drama of return and reunification: The overcoming of obstacles.

It must be left to far better storytellers than myself to imagine what this narrative might look like. Right now, it requires the most fanciful imagination. But if Zionism has taught us anything, it is that reality begins with a dream.

![]()

Banner Photo: NatanFlayer / Wikimedia