But if you’re a small, embattled Middle Eastern country, it’s not much fun.

On October 1, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addressed the UN General Assembly. His topic was, unsurprisingly, the Iranian nuclear program and the need for the world to act in order to stop it. “I want there to be no confusion on this point,” he told the assembled delegates. “Israel will not allow Iran to get nuclear weapons. If Israel is forced to stand alone, Israel will stand alone.”

Immediately, and again unsurprisingly, he was dismissed as a global spoiler, with the New York Times editorial board warning that his approach “could be disastrous if Mr. Netanyahu and his supporters in Congress were so blinded by distrust of Iran that they exaggerate the threat, block President Obama from taking advantage of new diplomatic openings and sabotage the best chance to establish a new relationship since the 1979 Iranian revolution sent American-Iranian relations into the deep freeze.”

It is, of course, very widely believed among supporters of Israel—and among some opponents, one imagines, though they are unlikely to ever admit it—that it is not only a reasonable supposition but practically a moral certainty that Israel cannot and will never get a fair hearing at the UN or from the international community in general. Indeed, Netanyahu all but said as much in his 2011 speech to the General Assembly, noting that the Lubavitcher Rebbe once referred to the international body as “a house of many lies.”

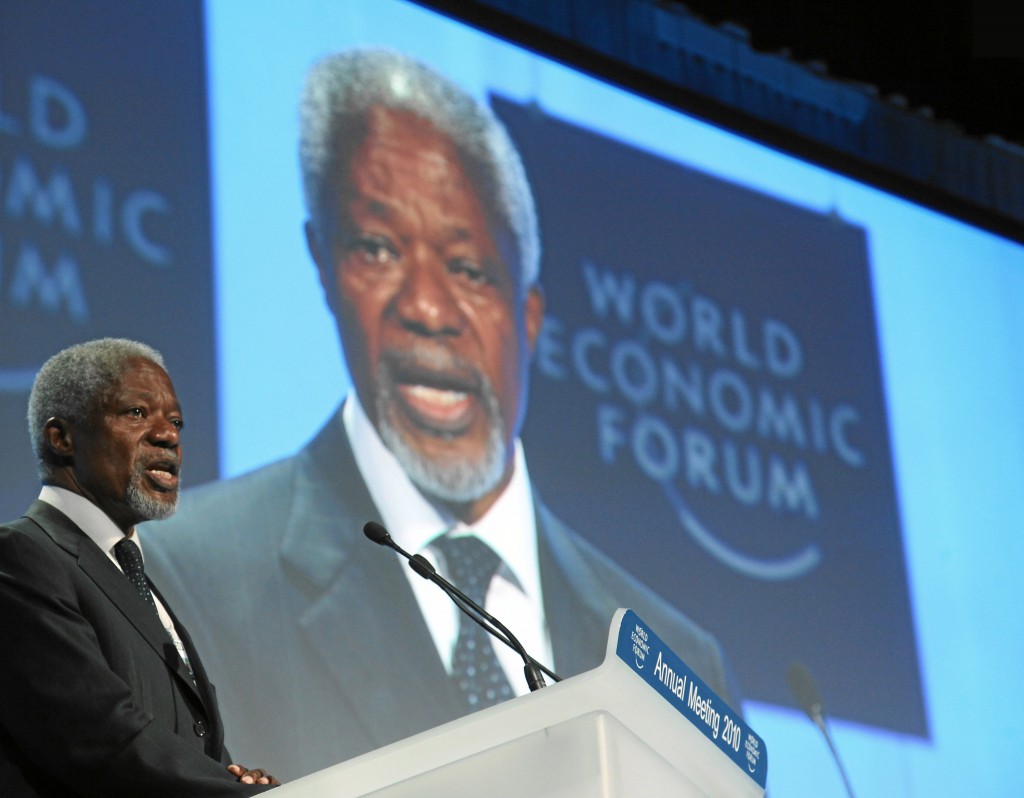

Most Israelis likely agree with this, as well. But however fervently they agree, there always remains a nagging doubt. This doubt was expressed fairly well, ironically, by one of the UN’s former leaders. In 2002, with Israel deep in the horrors of the second intifada and Ariel Sharon’s Operation Defensive Shield at last fighting back against Palestinian terrorism, international condemnation of the Jewish state reached a fever pitch. Then-UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan summed up the general attitude by asking, “Can Israel be right and the whole world wrong?”

This was a fairly ugly question in and of itself, given that there is something unseemly about the leader of an international organization pitting the entire world against a single nation. It is also worth pointing out that even a first-year philosophy student knows that truth is not determined by crowd size.

Yet few can deny that there was something in what Annan said. Israelis, Diaspora Jews, and people from all communities who harbor pro-Israel sentiments are constantly challenged by the fact that, quite often, it seems that practically everyone in the world believes Israel is wrong. One often has the sense that politicians, NGOs, intellectuals, artists, professors, students, activists, diplomats, and experts of all political stripes agree on only one thing: Israel’s policies, society, culture, politics, and even very existence are deplorable, offensive, or evil.

As an Israeli, and thus something of an object—albeit a decidedly minor one—of all this opprobrium, I can testify to the fact that it is not an easy thing to deal with. After all, if everyone in the world tells you that you are a horrible person, sooner or later you will probably start to believe it. However strong our convictions may be, we have all, at one time or another, found ourselves asking Annan’s question: Is it really possible, we wonder, for us to be right when everyone is telling us we are wrong or worse?

For myself, I was gratified to discover that this question had already been asked and answered over a century ago, when the State of Israel was still a dream in the minds of a small group of activists and thinkers. And in one of the acerbic little ironies history periodically throws our way, it had been asked and answered in Mr. Annan’s own words.

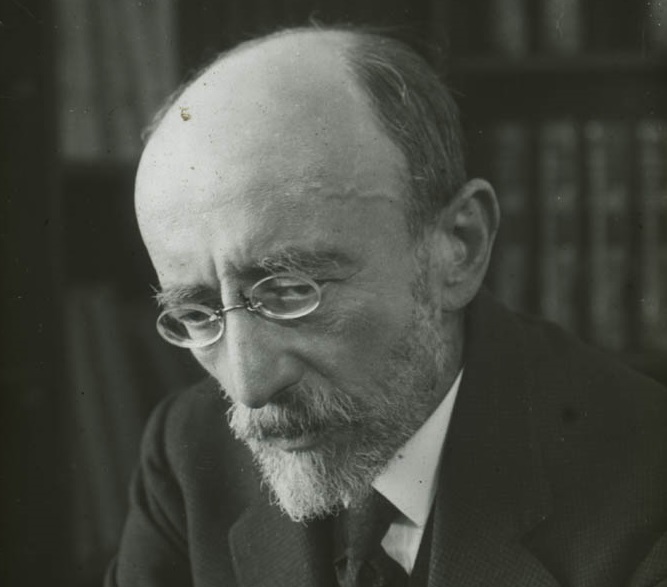

Asher Ginsburg, far better known by his pen name Ahad Ha’am (“one of the people”), was one of the most important Zionist intellectuals of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A critic of Theodore Herzl’s political Zionism, he believed—wrongly, it turned out—that Herzl’s vision of a mass exodus of Europe’s Jews to then-Palestine was unrealistic and likely impossible. Instead, Zionism ought to concentrate on building an autonomous Jewish community in the Land of Israel. The primary role of this community would be to act as the spiritual and cultural center of world Jewry, fostering a secular Jewish renaissance founded on the revival of the Hebrew language. To a relatively large group of activists referred to as “cultural Zionists,” he became something of a guru, a secular rabbi so respected that, when he moved to Tel Aviv late in life, the street on which he lived was periodically closed down so as not to disturb his sleep.

Ahad Ha’am wrote several enormously influential essays, many of them critical of trends in Jewish and Zionist culture. In particular, he was bitterly opposed to both assimilation and religious isolation, rejecting both the ghetto and the Emancipation as equally undesirable. But one of the greatest of all his writings concentrated on an entirely different subject: The insidious psychological influence of anti-Semitic myths on the Jews themselves.

In the 1892 essay entitled “Some Consolation,” Ahad Ha’am asked Annan’s question in practically identical terms. “Since everybody hates the Jews,” he wrote, “can we think that everybody is wrong and Jews are right?” And like today, Ahad Ha’am noted that the question could not be easily dismissed. “There are many among us Jews,” he wrote, “on whom a similar question half-unconsciously forces itself.”

Ahad Ha’am’s answer was a simple one, but he used a very singular proof to make his case—the blood libel. It was indisputable fact, he noted, that for centuries, the overwhelming majority of the non-Jewish world believed that the Jews held hideous ceremonies in which non-Jewish children were murdered and their blood used in unspeakable demonic rites. And it was equally indisputable that, throughout all those many centuries, every Jew in the world knew this was a deranged fantasy.

“Yes,” Ahad Ha’am concluded, “it is possible” for the Jews to be right and the entire world wrong. “The blood accusation proves it possible. Here, you see, the Jews are right and perfectly innocent.”

As the title of his essay suggests, Ahad Ha’am took “some consolation” from this fact, and with good reason. But there is a darker side to this consolation, because it also reminds us that, although we may know that we can be right while the world is wrong, it does nothing to prevent the world from continuing to believe otherwise.

Everyone reacts to this in different ways. In the Diaspora, it often means a perpetual struggle against those who believe that because “the whole world” believes the worst of Israel, it must be true. A small minority simply gives in and, effectively, joins the other side, concluding that “the world,” if only by virtue of superior numbers, must be correct. Others defy it outright, insisting instead that Israel is always right while the world is always wrong. Still others simply trudge quietly on, keeping their heads down and hoping for the best, occasionally making small and private expressions of their Zionism.

For those who support Israel publicly, it is rarely much easier. Activists and members of pro-Israel groups do their best to use reason, logic, and public relations to change people’s minds, often thanklessly. Students and other young people often suffer intimidation, insult, and occasionally violence on college campuses and other academic institutions, where hatred of and contempt for Israel is depressingly widespread. They are met equally often with indifference to their predicament, usually from faculty or administrators who have accepted, perhaps unconsciously, Kofi Annan’s admonition, utterly unaware that Ahad Ha’am discredited it more than a century ago.

But perhaps the harshest effect is on Israel itself. From the average man in the street to the prime minister’s office, Israelis are, for the most part, convinced that the world has never and will never accept Ahad Ha’am’s argument. This has resulted in one of modern Hebrew’s most popular but depressing expressions: kol ha’olam negdeinu. “The whole world is against us.”

It is not an exaggeration to say that this sentiment is quite widespread in Israeli society. In fact, a 2011 survey showed that 56 percent of Jewish Israelis agreed with that phrase. And the response to this feeling is usually the same: We have to go it alone. Indeed, Israeli leaders say so explicitly and often. In 2005, then-prime minister Ariel Sharon said, “We know that we can only rely on ourselves.” As recently as September of this year, Prime Minister Netanyahu and Defense Minister Moshe Yaalon both used almost precisely the same words. “At the end of the day,” Yaalon said, “we have to rely on ourselves.” “If we are not for ourselves,” Netanyahu asked, echoing a line from the rabbinical text Pirkei Avot, “who will be for us?” He repeated this theme in his UN speech: “If Israel is forced to stand alone, Israel will stand alone. Yet, in standing alone, Israel will know that we will be defending many, many others.”

Israel, it must be said, has some good reasons for feeling this way. Perhaps the most traumatizing was the run-up to the 1967 Six Day War, when, surrounded by Arab armies primed for invasion, Israel found itself completely abandoned by the international community, including those who had been its closest allies. US President Lyndon Johnson told Israeli diplomats that “Israel will only be alone if it goes it alone.” But in the end, Israel felt it was already alone, and had no choice but to go it alone in response. It scored its greatest military victory as a result, but the sting of abandonment and resulting sense of injustice has never gone away.

Worse still, many Israelis feel that the same thing has happened over and over again with depressing regularity: In 1972, Israelis watched as the Olympic Games went merrily on in spite of the massacre of 11 Israeli athletes. In the months afterward, European governments did little or nothing against the perpetrators, prompting Israel to launch its own operation to hunt down the terrorists involved. In 1973, Syria and Egypt launched the Yom Kippur War in an even more blatant act of aggression than 1967; yet it was Israel that stood condemned in international opinion, and found itself abandoned and isolated diplomatically. In 1975, the UN summarily declared Zionism a form of racism, effectively announcing that the Jewish people have no legitimate national rights and Israel no right to exist. In the early 1980s, during the first Lebanon War, attention overwhelmingly concentrated on the travails of the Palestinians, completely ignoring the decade of Palestinian violence that prompted the war in the first place. During the first intifada, Israel was overwhelmingly regarded as an oppressive tyrant, without regard to the possible security implications of withdrawing from the West Bank. And, of course, after an unprecedented Israeli offer of peace was refused in 2000 and a Palestinian terror campaign of unprecedented scope began, Israel—indeed, the world Jewish community in general—found itself not simply criticized, but demonized all over the world.

This is not to say that Israel did everything right in each of these instances, or that some of the criticism that came its way was entirely unjustified. It is simply to point out that neither of those considerations was particularly relevant to the overall treatment of Israel by “the world.” The verdict, it often seemed, had been handed down before the accusations were made. We are not always right while the world is wrong, but it happens often enough to give us considerable pause.

There is a reasonable case to be made that Israel is not nearly as isolated as it once was. And indeed, there are times when the universal hatred of Israel is mostly lip service. Military ties have been fostered with India, economic relations with China are expanding, Europe is less hostile than it has been in the past, worsening ties with Turkey have led to improved relations with Greece, the United States remains firmly in Israel’s corner, and many believe that even our famously troubled relationship with the United Nations is slowly changing for the better.

But there are more than enough counterexamples to continue reinforcing Israelis’ general impression that the whole world is against us: The international community loathes Benjamin Netanyahu, but woos the president of theocratic Iran; it accuses Israel of committing mass murder in Jenin, and does not apologize when it is revealed that the supposed massacre never happened. Israeli bodies are torn to pieces by suicide bombs, and world leaders inquire whether Yasser Arafat has batteries for his cell phone. The Goldstone Report is feted around the world, and no one seems to notice when its own author repudiates its findings. Israeli soldiers are accused of deliberately slaughtering innocent activists on the Mavi Marmara, and when proof emerges that it was, in fact, the activists who attacked the Israelis, the world seems to do its best to ignore it. The Iranian nuclear program appears to worry no one until Israel threatens war, at which point Israel is accused of war-mongering. One could go on in this vein for hours.

As in the Diaspora, Israelis deal with this in different ways. There is a minority that ultimately takes the side of “the world,” adopting an adversarial position according to which nothing Israel does can possibly be right and Israeli society can never be anything other than a monstrously evil system of oppression and violence. Most of these people fall on the extreme Left, but the extreme Right has adopted an equal and opposite position on the subject, according to which nothing Israel does can be wrong, and every Israeli action, however wrongheaded or ill-conceived, is brave defiance of an evil and unjust world.

Most Israelis, however, have come to agree with David Ben-Gurion, who once remarked that “It doesn’t matter what the goyim say; it matters what the Jewish people do.” Israel, they feel, must do what it needs to do, and act in its own best interests whether “the world” approves or not. Ultimately, it is up to Israel itself to decide whether it is right or wrong, because there is no chance that it will ever get anything like a fair hearing from others. Even the United States, a good a friend as it is, must answer to political forces and diplomatic considerations that are not always conducive to a just assessment of Israel or its actions.

There are some, perhaps many, who consider this a noble thing, and admire Israel’s insistence on keeping its own counsel and its refusal to accept unfair and unjust criticism. And it is not impossible that there is, perhaps, something like historical fate at work. The role of the prophet is one of the most revered in traditional Judaism, and it is, of course, the role of the prophet to stand against social consensus, denouncing injustice, idolatry, and evil however powerful its practitioners may be. Many cultures have similar archetypes, but in Judaism it is notably, perhaps uniquely emphasized. Indeed, without becoming unduly mystical, it is difficult to ignore the fact that, for the entirety of its history, the Jewish people have tended to keep their own counsel, to be a people apart, to not apologize for being different, and to “go it alone” despite the opposition and even hatred of the rest of the world. Perhaps the hope that a modern Jewish state would not have to do the same is asking too much.

But it must be admitted that there is a heavy psychological cost to never being able to fully trust other people. And having to go it alone, however necessary, is a lonely fate. Israel’s political establishment, like most political establishments around the world, probably does not particularly care about being liked. But many Israelis do, and those who do not are nonetheless bitterly resentful of the world’s tendency to deal with Israel in what they consider to be a blatantly unjust manner. Indeed, most people would agree that the feeling that one will be hated no matter what one says or does is a painful thing to accept. Even if you know it is possible that you are right and the whole world is wrong, it is still not a happy thought. Ahad Ha’am was right when he referred to it as “some consolation.” It is some consolation, but not very much.

![]()

Banner Photo: Kobi Gideon / Flash90