Mishy Harman built a successful Hebrew radio show modeled on This American Life. Now his unusual explorations of Israeli life are available in English too—opening a remarkable window to a remarkable people.

Before we meet, I have already formed an impression of Mishy Harman from his voice, which narrates the English-language podcast Israel Story, a remade version of his Hebrew-language Army Radio show Sipur Israeli. This is the strength of any radio show, where the thrill of listening lies—in the voice. Harman’s has something endearing and boyish about it. It is a bit goofy and off-kilter, but with a sense of good humor, as if it doesn’t take itself too seriously. The voice may meander and ramble a bit; it may go here and there; but it is interesting to follow as it talks to a comedian searching for the love of his life through setups by relatives in the West Bank, or to all the people who work and eat at a 24-hour pancake house. Even if the purpose of the story it tells isn’t entirely clear from the outset, we don’t mind; it is engaging. At least, these are the impressions I jotted down so I could compare them to the person himself.

This is one of the charms of radio: The audience only knows speakers from their voices, without the usual preconceptions people will have when meeting others and judging them by their appearance. Harman himself told me, “That’s the cool thing about radio; it circumvents all kinds of labels.” He added that, particularly in Israel, whenever you see a person, you almost immediately label them. But in radio, especially in our visually saturated culture, there is something intimate about hearing a voice speaking and feeling as if the speaker is addressing you directly, in person, telling you something. As Julie Subrin, the producer of Vox Tablet, which hosts Israel Story, said, “The way most people listen to podcasts is with headphones, more like this person is speaking to you, so you are more receptive in that intimate medium.”

In the tone of Harman’s voice, there is something similar to that of Ira Glass, who narrates the acclaimed radio show This American Life, a major influence on Israel Story. It is irregular, with the up and down and back and forth of a regular person talking. This persona of the average person speaking is purposeful on the part of both Harman and Glass. In a recent interview, Glass said of his voice,

I haven’t noticed people who sound like me, but I have noticed people trying not to sound like the sort of traditional public radio news sort of performance, and just talk more the way they actually talk. When I hear Jad Abumrad, who is the host of Radiolab, I don’t think he sounds like me at all. I can tell that he heard me on the radio and was just like, “Oh, I will just try to talk like myself.” I definitely think there are more people doing it.

There is no doubt that This American Life is a major influence on Israel Story. In many ways, Israel Story incorporates ideas from This American Life, but with an Israeli twist. Israel Story has episodes about a woman who went from her childhood home in Long Island to Alaska to study sea otters, gave birth in Alaska to a child with Down’s syndrome, then adopted another Down’s syndrome child and made her way to Safed in northern Israel. Another show features a young man who has written letters to all the female members of the Knesset. Harman meets him at the shiva for his 99-year-old grandmother, a former Knesset member for the Labor party. Another is the story of an Israeli man who feels he needs to start over by leaving Israel to open a buffalo farm in Wisconsin and curses at his herd in Hebrew. There are stories about people who find their birth parents, the love lives of Harman’s Jerusalem neighbors, and the search for the Aleppo codex, a 10th-century manuscript of the Bible, parts of which had mysteriously disappeared by the time it was taken from Syria to Israel. All stories have the charm of people talking, as though they were speaking to a friend, but with well-crafted editing, music, and sound effects.

The creators of This American Life are well aware of Israel Story. In fact, Harman tells me that the first time he met Ira Glass, Glass got out of his chair and said to him, “Are you the Israelis that are ripping off our show?” Despite the joke, Glass has been quite supportive of Israel Story, even attending the live show “Herzl 48,” held at the JCC of Manhattan.

Subrin described the character of radio storytelling as creating “an intimacy,” the sense of “a person telling their story in an authentic way, an immediacy.” She explained that this makes the listener “more open to them, to different perspectives,” adding that a radio show is effective when an interview subject “is thinking out loud with us, present, not a rote performance that they don’t have to think or feel about.” As Harman put it, the goal of his show is to tell “stories on a human level.”

Harman asked me to meet him at Café de Paris on Sderot Ben Maimon in the Rehavia neighborhood of Jerusalem. I was a bit unsettled by this, because the café was the site of a March 9, 2002 terror attack in which 11 people were killed. The last time I was in Israel, I ate my last meal in a restaurant on Emek Refaim that had also been the site of a terror attack, so it seemed odd to be starting my trip at a place that had such a past. But it also seemed appropriate, in keeping with the way Israel Story presents the reality underneath the surface of things.

When I mention the 2002 bombing during our conversation, Harman tells me he’d been at the site about 45 minutes prior to the attack. He was in the army at the time, and felt conflicted about the tasks he had been assigned to do during the week. As a way of atoning for his actions, he regularly attended Saturday night protests at the prime minister’s house, a short distance from the site of Café de Paris. That night, after the protest, he walked past the site with his brother.

When I walked into the café, I saw a young man with a shock of bushy brown hair, though he was quick to inform me that his mother insisted he have it cut before his trip to the U.S., so it was actually shorter than usual. Underneath the hair, Harman’s glasses are almost absurdly large and round, with brown eyes underneath. A caricaturist would have fun with features so suited for visual exaggeration. He was wearing a bright fire-engine red Patagonia down coat, with small red patches where the down was making its way out of the sleeves. When the sun came out, and the coat came off, he was wearing a plaid button-down shirt with a t-shirt peeking out from underneath. His shoes were tan Birkenstocks (or perhaps the Israeli equivalent—Naots) with garish bright pink socks. Eccentric? A bit. Basically, Harman looks like someone who would be comfortable sleeping in his car as he drove cross country.

Which is precisely what he did when he finished a stint as a teaching fellow at Harvard—where he earned his BA—in the summer of 2010. Before returning to Israel to start a doctoral program at Hebrew University, Harman drove across the U.S. with his dog Nomi, staying in the homes of former students along the way. Altogether, he traveled through 32 states, spending many nights sleeping in his car. But when he found a place to stay, he discovered that the family origins of his students were diverse and fascinating. There was an El Salvadoran family of illegal immigrants in north Texas; a seaside mansion in California; a pueblo in New Mexico; and a trailer park in Pittsburgh.

In each place, he usually arrived late at night, and when he got up in the morning, the mother of his student was often waiting to make him breakfast and wanted to talk to him. He says that he “felt ambivalent” about having to sit and listen to these stories, which would “gobble up a whole morning” when he had just one day to see Santa Fe or Los Alamos; but he felt that if anyone was “kind enough to put me up with a dog, I want to be friendly and polite.” So he just “got into these long conversations with the moms” when they would start “telling these long stories.” He heard all kinds of stories, such as a woman whose former dreams of a career as a psychologist had been waylaid by having kids and a woman whose brother committed suicide. Of the latter, he says, “I don’t know why she chose to tell me but she did. I am very honored when people share their stories, touched by them really.”

Harman’s narrative of how Israel Story began is that he listened to This American Life while driving because he found the repetitious nature of radio in the Bible Belt not to his liking, then decided to create the show while in Vicksburg, Mississippi. But I suspect that the stories told by the mothers of his students and his need to listen contributed just as much. Harman became a vehicle for people who wanted to tell their stories, which is precisely what he does on his show.

Though he says he had limited human interactions other than the homes he stayed at, while sitting with him at Café de Paris, one sees another reason why people would simply start talking to him—his dog. Nomi is a brown dog with a kind demeanor; I can’t imagine her ever frightening anyone. I have never had a subject bring a dog to an interview, but then again, Harman also brought her to class at Harvard. It was helpful to have her along, because through her, I got to see Harman at work. As we sat in the sun and he spoke at such great length, a great number of people came up to speak to us or, more accurately, to Nomi.

Even her name speaks volumes about Harman and where his show comes from. Harman told me that she was named after his aunt Naomi. But no less a personage than a Member of Knesset told me that the dog’s namesake was herself a Member of Knesset. When I went to interview MK Michael Oren for another article, he asked about the pieces I was writing and I mentioned Israel Story. Oren asked me if I knew that Harman’s grandfather Avraham served as Israel’s ambassador to the U.S. from 1959-1968, and that his aunt was Naomi Chazan, a longtime Member of Knesset for the Meretz party. I didn’t, but I wasn’t surprised. Harman is an extremely well-connected person in both the U.S. and Israel. In fact, when we stop to park his car for a rehearsal in Tel Aviv, another driver stopped to talk to him. When I ask Harman who he was, he tells us casually, “Oh, my sister’s old boyfriend Dovi Gilhar. He has the biggest morning talk show in the country.” Telling me about his trip with his mother, Dorothy Gitter Harman, to visit colleges, he says he had lunch at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, because his mother had gone to graduate school at Harvard with Elaine Pagels, one of the fellows at the Institute. Dorothy is now a representative of Harvard University Press in Israel, while Harman’s father David is a professor of education at Hebrew University. His sister Danna Harman is a correspondent for Haaretz and, of all things, the model for actress Jennifer Connelly’s character in the movie Blood Diamond, which was partially based on the time Danna spent in Africa as a foreign correspondent. His brother Oren is Chair of the Graduate Program in Science, Technology, and Society at Bar-Ilan University and author of The Price of Altruism, which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. And his late grandmother Zena Harman was a Labor MK in the 1970s.

Since his family’s involvement in politics never came up during our interview, I asked about it later via email. Harman replied, “There is no doubt that my family’s involvement in politics has had a tremendous impact on me. My strongest childhood memories are of heated political arguments during Shabbat dinners; even though, at the end of the day, everyone basically voted for the same party.” I can see that, with such a family, conversation and listening to stories would be part of growing up. Harman added, “I would have to think about it more, but my grandparents’ and parents’ sense of social responsibility, and the idea of listening to peoples’ stories and helping them is a very big part of me.”

Sitting with Harman and Nomi, I had a great opportunity to see Harman at work on a story. We had the best service I’ve ever had in Israel, since the wait staff kept coming over to check on whether Nomi had enough water. In addition, there was a woman with a baby who wanted to introduce her infant to a friendly creature, a woman from New York who agreed to go to the “Herzl 48” show when we told her about it, the guy with the bookstore around the corner, and the bald man who had a menacing look about him—like he might have killed a few people—but walked up to Nomi and said, “Look at her. She is worth more than any person here” and then hugged her.

We also had a long talk with the hummus guy. Harman knew exactly who he was, and via Nomi started a casual conversation with him. He was Rami Majar, the son of the owner of Ta’ami, a legendary Jerusalem hummus place in the center of town, where Harman’s mother took him every Friday while he was growing up. The owner, an immigrant from Bulgaria, had lost three fingers in the War of Independence, and was feared by customers. If they sat and read the paper too long, he would yell at them. Once a woman asked him his secret ingredient. He yelled across the store that he urinated in the hummus to give it flavor. He opened a store in Tel Aviv with a partner who would pick up the hummus from him each morning; but somehow, once it got to Tel Aviv, it didn’t taste the same. Finally, he rode along one morning to see what the problem was, tasting the hummus every few meters along the way. He claimed that at Sha’ar Hagai, 20 kilometers from Jerusalem, the taste changed; something in the Jerusalem air, he said, gave it a flavor that couldn’t be replicated or even survive outside the city. Harman schmoozes with the son and asks him about these stories, acting as though he doesn’t know anything or have any interest beyond mere curiosity. The son, now wealthy through his family’s real estate investments, is happy to answer Harman’s questions. At 61, he tells us proudly, the hummus restaurant is as old as he is, and opened on the day of his circumcision in 1954. Harman gently asks about the store owner in Tel Aviv, and it turns out the problem wasn’t just the different air in another city, but that the partner was a drinker and unreliable.

When the man leaves, I tell Harman I am impressed with how he asked the questions without letting on that he had been tracking the story for a segment Israel Story will be doing on hummus and spoken with a number of the other principal characters. The conversation was so casual and friendly, and the man so unguarded and open, answering Harman’s questions freely, never suspecting he was a journalist and Harman never giving it away. I commend him for his prowess, and he replies, “I am less calculated than you think I am.”

This interaction, seemingly a random conversation, yet actually a careful eliciting of information, seems typical. Harman may not be calculated, but he is a person who, though he may sleep in his car, knows how to find a bed when he wants one.

This talent helped get Israel Story off the ground. In short, Harman got the show by just doing it. After his trip across the U.S., he proposed it to his friends Shai Satran, Yochai Maital, and Ro’ee Gilron in Shai’s living room on Lincoln Street in Jerusalem. They got a meeting with Yaron Deckel, head of the army radio station Galei Tzahal, and met with Nancy Updike, a producer of This American Life who was living in Tel Aviv with her husband, a Newsweek correspondent. They were able to meet with Updike through mutual friends, and Harman says that they asked her “literally the most basic questions. How to choose stories, how to write, how the process worked.” From there, Updike put them in touch with Ira Glass and the group spent a few days in New York with the This American Life team, “observing their process” as Harman puts it.

These observations served them well. Harman wanted to change the way radio is done in Israel by producing carefully taped and edited stories in the style of This American Life. As he explains, “Most of the radio here is interviewers with an open mike speaking over the phone to a politician, yelling at them about why they are supporting a bill they were opposed to two weeks ago.” Harman’s sense before he started the show was that “Israel is a storytelling nation and diverse. This could catch on.” He explains that there is a high number of radio listeners here because of the high number of cars per capita. And in Israel, radio has always been a connective vehicle. A big fixture of radio in the early days of Israel was a show in which people would look for relatives, to try to see if they could find those who had survived the war. An announcer would read names of those seeking their relatives and instruct listeners to write to a centralized address at the Jewish Agency if they knew anything.

The two radio stations in Israel—Kol Yisrael, run by the government, and Galei Tzahal, run by the army—did not have storytelling like NPR in the U.S. After the group’s meeting with Glass and NPR, they had an Indiegogo crowdfunding fundraiser, and Glass made a video to support them. Through Updike, they reached out to Israeli writer Etgar Keret and, for the first episode, Keret met with them and recorded a story.

Another early supporter of the show was writer Matti Friedman, a former AP journalist and author of the book The Aleppo Codex, about a 10th century manuscript of the Bible brought to Israel with pieces mysteriously missing. The book came out around the time Israel Story debuted in 2012; and Friedman says the show “gave me a zoom, I went out to interviews and I scripted it.” He says the show was done with “a ton of attention paid to detail, tightly controlled product, well-edited music carefully selected.” It was “very carefully done, a labor of love. They don’t mess around.” For him, the process was enjoyable because radio is “a whole different way of putting together a story. … The way a person’s voice sounds is important, you can create atmosphere using music, audio, clips. There are tricks you don’t have as a print journalist.”

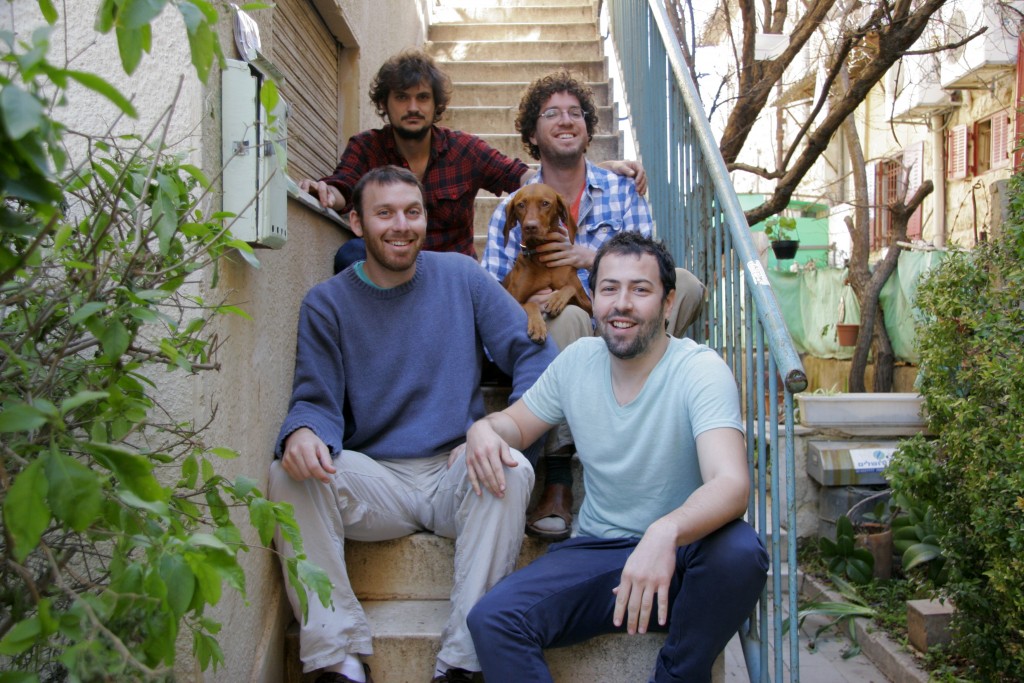

The four creators of Israel Story (clockwise from top left): Yochai Maital, Mishy Harman, Shai Shatran and Ro’ee Gilron. Photo: Israel Story

As a journalist, Friedman says, you are “trained to see the country in a certain way. You are trained to see cliché.” Coming from him, this is an understatement, as his recent piece on the Associated Press’ instructions to their reporters shows. He explains that “as a reporter you see this country, go to the gas station, talk to people, and then sit down and write an article that describes a completely different country that consists of clichés that you have been taught to believe in.” Israel Story, he says, is different. Its writers “view the country as it exists at ground level.” One of Friedman’s favorite episodes is about three blind Arab brothers. The episode had “nothing to do with them being Arab. They just happen to be. It is exactly what we need.” He is pleased to be able to listen to a show whose “idea is stories that are about this place but not the usual stuff.”

Friedman adds that it is “an accomplishment to put this together,” because the team of four had to be “dedicated for a long time before they saw results. … I hope they grow and I hope they retain the chaotic energy that is the fuel for the whole enterprise.”

The question is, now that the Israel Story staff has grown from the original four to eleven, will the show retain the “chaotic energy” that originally fueled it? Certainly, the four friends were the secret of the show’s initial success. They share many characteristics: American parents involved in academia, similar political views, connections to the Conservative movement in Israel, and a desire to do stories outside of their personal orbit. Harman himself says they were “concerned that their homogeneity would restrict things.” Because they were so similar, they had to come up with gimmicks, to “manufacture a situation,” in order to have a variety of places and types of people represented on the show. They did the 24-hour pancake house story; “Herzl 48,” in which they knocked on the door of those living at that address in 37 of the 54 Israeli cities which have a Herzl Street; and a story about 12 schools in 12 different places with radically different philosophies, including Bedouin, settler, and “Left-wing secular fancy anthroposophic” schools. Harman said that the show aims for “a wide range of experiences, not to only present a cherry-picked sliver of Israeliness.”

In order to keep the show strictly documentary, they are also careful not to add sound to a piece. Harman explained that they did a piece on a couple from a Carlebach community in Mevo Modi’im in which they spoke about love and their relationship as the husband was dying. The man died the week the show was released and the Israel Story team went to the funeral. Harman says there were people singing and playing guitars, and the team recorded the proceedings with their IPhones to avoid being intrusive. When they listened to the recordings, the sobbing and crying of the mourners could not be heard. The team had to decide whether to add these sounds to the recordings. They ultimately decided against it, because, as Harman put it, “We know the sounds would not be natural and that made it wrong.”

Maya Kosover, Yochai Maital and Dor Danino at the planning session for season three of Israel Story. Photo: Ro’ee Gilron

It isn’t always easy to tread this fine line between “manufacturing a situation” and the desire for documentary realism. Because Arabs are 20 percent of the Israeli population, it was felt that they should be represented in the “Herzl 48” show, but it was unlikely that an Arab would be living on a street named after Theodore Herzl, since Arabs are likely to areas that typically don’t have Herzl Streets. Though they were hoping to find an Arab in Akko or Lod or Ramle, Harman says, “We are a documentary enterprise and we can’t manipulate the situation to such an extent that it is not true.” The team was successful, however, in finding an Arab in a town which is 97 percent Jewish—a man working in a pharmacy in Zichron Yaakov.

At the rehearsal for the “Herzl 48” show in Tel Aviv we heard his story, and others: Stories from an American football fan in Jerusalem; from Bnei Brak, where Herzl Street was renamed Rabbi Schach Street; and from Ofakim. To Israelis, Ofakim is the most desolate and destitute of places, one where Jews from Arab countries were settled without much choice in the matter. Yet it is there that the Israel Story team found a man who, despite not being able to pay his electric bill, says he is the happiest man in the world. We watch a video of this man, Shimon Moshe Peretz, singing a song about his town, and in a few moments, even though he is not actually with us in the room, and even though it’s late and we’re tired, all of us are singing along with him. Corny, yes; but sincere all the same. The enthusiasm of this randomly chosen man and how much he cares about the place he lives comes through.

Right now, Harman is struggling to finish his PhD “so I can devote all my time to this.” His dissertation is on an Swiss bishop named Samuel Gobat, who did missionary work in Ethiopia before serving as Protestant bishop of Jerusalem in the 19th century. He has written the chapters, but is struggling with the introduction and conclusion. He feels like he is telling the man’s story, but there is “no argument in the thesis,” and that a thesis is often something “imposed.” He has come to see his biography of Gobat as a “long and heavily footnoted radio story.” Harman adds, “We tell ourselves a grand narrative of our lives to make sense of our choices.” When I ask why he needs to finish his dissertation if he has found something else he wants to do, he says simply, “I always want to finish. It’s a good thing to finish.”

There’s no doubt, however, that Harman isn’t finished with his show. And perhaps the main reason is how much he and his friends like it. Yochai Maital, the senior producer, said in an email that he loves many things about it.

For one thing, not only do I get to meet many interesting characters that I would never meet otherwise, I have the perfect excuse to spend lots of time with them and ask them bucket loads of questions without it being weird. I feel it is a great privilege and responsibility to give voice to others, especially others that are not usually heard. I love the intimacy that is created in radio, and how radio works the imagination. I feel like the kind of radio we do takes the best of two worlds—prose and cinema.

“Stories belong to everyone, we just happen to tell them,” Harman told me that day at Café de Paris, where he kept speaking for so long that my arms got completely sunburnt. I didn’t care about the sun though, because I got the chance to hear a great story from a master storyteller and communicator.

![]()

Banner Photo: Israel Story