Partisans on both sides of the Arab-Israeli conflict have been trying for decades to claim Martin Luther King, Jr. as an advocate for their side. Where does the truth lie?

The enemies of Israel—the enemies, effectively, of the Jews, let’s make no bones about it—stop at no distortion of history or corruption of the mind to achieve their goal of demonizing the Jewish state. The whole “washing” concept, which attempts to turn, via alchemies of linguistic play and theoretical inversion, virtues into villainies, exemplifies this intellectual corruption: Israel’s proud history of gay rights, for example, is denounced as “pinkwashing,” while other “washings” attempt to make every liberal good of Israeli society, its belief in freedom and tolerance, into a covert form of oppression. And like so many who have done so much ill before them, these demonizers of the Israeli state and traducers of Judaism think that what they do is good. They imagine they improve the world. They are soldiers for “peace and justice.” And in modern American history, there is no soldier for peace and justice—no Christian soldier—greater than Martin Luther King, Jr. So King, in just one more in a parade of historical distortions, must be posthumously turned against Israel.

In fairness to “critics” of Israel (which one offers out of regard not to them, but to oneself), where King very narrowly is concerned, they do not appear to have initiated the debate. However, contention over just what King’s relationship was to Jews and Israel, his stance in regard to Zionism, and what might be his position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict today, does not arise out of a vacuum. It is one aspect of the modern history of the relationship between Jews and African-Americans, as well as more contemporary ideological contentions.

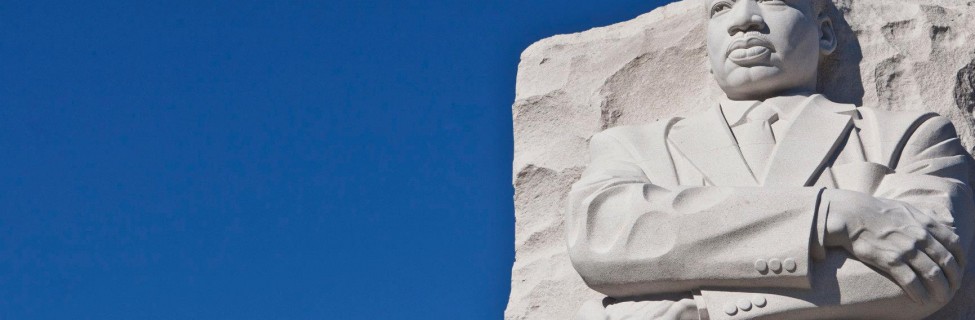

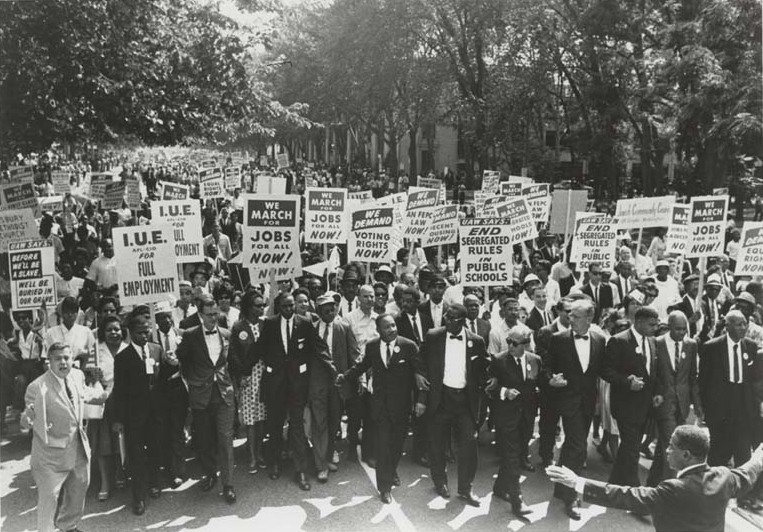

Martin Luther King leads the march on Washington. Among the marchers is Rabbi Joachim Prinz. Photo: American Jewish Historical Society / Wikimedia

Many Jews rightly feel a special connection to black Americans and their struggle for civil rights. Jews were prominent in the founding and—for decades—the leadership of the NAACP, and were substantial supporters of many other black-led civil rights organizations. Their participation in the civil rights movement was greater than any group except African-Americans themselves. From there, the relationship becomes more complex, from black accusations of Depression-era ghetto exploitation and growing post-‘60s Jewish middle-class racism to Jewish grievances over African-American anti-Semitism among more radicalized Afro-centric organizations, as well as the mainstream post-King leadership, and in academia and the arts. As good and balanced an article-length overview of all these issues as one is likely to find can be read at the Jewish Virtual Library.

One can divide this dispute into two separate but related conflicts. One is the presence of two minority and historically oppressed cultures located in adjacent social spaces. This proximity produces social alliance, but also competition. A disparity in progress produces tension and conflict. This is a phenomenon seen all over the world. If the social alliance has been profound, the historical oppression intense, long, and enduring for both, and the contact continual, as is the case between African-Americans and Jews, the relationship can easily become contentious.

The second conflict has origins of its own, but is fed by the former, and that is post-colonialism—not just the theory, but the historical reality that gave rise to the theory.

These developments, particularly the latter, have led to a decrease in African-American support for Israel among those far-Left progressives most influenced by post-colonialism. This alienation is promoted by far-Left organizations—including some Jews—such as Students for Justice in Palestine, who attempt to tie campaigns like the current Black Lives Matter movement and anti-Israel agitation to the legacy of the Civil Rights movement. One defensive response to this among some Jews has been to grasp at the mantle of King and his documented support for Israel, his condemnations of anti-Semitism, and even his warning against attempting to mask anti-Semitism with anti-Zionism. The public record of King’s opposition to anti-Zionism, however, is slight. Thus, every year at the time of King’s birthday, controversy over the issue erupts anew.

Contemporary disputes over King’s views on anti-Zionism begin with Rabbi Marc Schneier’s 1999 Shared Dreams: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Jewish Community, which quotes from an apocryphal “Letter to an Anti-Zionist Friend,” supposedly published in a book entitled This I Believe: Selections from the Writings of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., of which no record has ever been found. The style of the quote is so ridiculous an exaggeration of King’s metaphorical tendencies that it might parallel an International Imitation Hemingway Competition parody of Papa’s prose. In just a few years, the fake was exposed by those displeased with its message. Fraudulent quotes on the internet are widespread, making the annual articles that set out to debunk the quote ubiquitous. Schneier, though taken in by the fakery, if that he was, continues to advocate for an alliance between activists for African-American social progress and supporters of Jewish nationalism.

The fake quote was not all, however. While anti-Zionists were successful in exposing as fraudulent one denunciation of anti-Zionism by King, another, important, if slender, piece of evidence has been corroborated.

For a very long time, King was purported to have replied to a young, more radicalized civil rights campaigner, at a dinner in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1968 (or 1967): “Don’t talk like that! When people criticize Zionists, they mean Jews. You’re talking anti-Semitism!”

The words were first reported in 1969 by Harvard scholar Seymour Martin Lipset, who was present when they were spoken. By 2004, with Lipset debilitated by a stroke (he died in 2006), two Palestinian-Americans published on the virulently anti-Israel website Electronic Intifada a strenuous attempt to cast doubt on the veracity of Lipset’s by then apparently unverifiable claim. They contended further that there was no evidence King had even been in Boston during the specified time period.

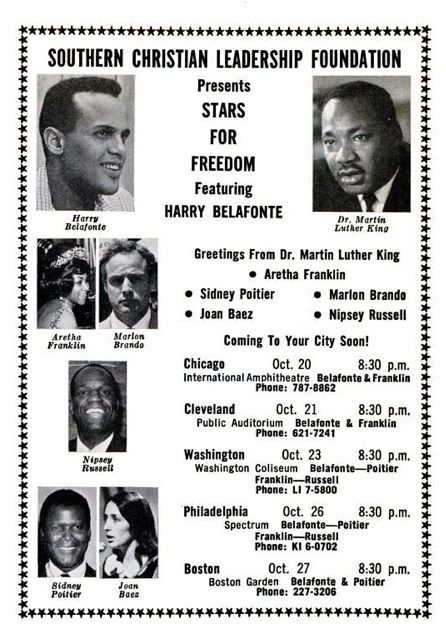

Martin Luther King criticized anti-Zionism at a benefit concert for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

In 2012, however, Martin Kramer published online the results of his attempt to verify King’s statement. It turns out that on October 27, 1967 King did attend a Boston benefit concert, headlined by Harry Belafonte, for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference Foundation. Anticipating his presence, an invitation to dinner in Cambridge was extended to King by a young Harvard professor—Martin Peretz, who went on to own and publish The New Republic (Peretz is now on the board of directors of The Israel Project, which publishes The Tower). Also among those present at the dinner was King aide Andrew Young. Prior to the dinner, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had promoted the kind of hateful, demonizing lies about “Zionist terror gangs” that are tragically commonplace today. It was in this context that “Lipset heard King rebuke a student who echoed the SNCC line on ‘Zionists.’” Asked by Kramer to confirm Lipset’s memory of the exchange, Peretz responded, “Absolutely.”

Andrew Young, for his part, went on to serve as President Jimmy Carter’s ambassador to the United Nations. He was asked to resign in 1979 after an unauthorized meeting with a member of the Palestine Liberation Organization that was contrary to U.S. government policy. Young responded by calling Israel “terroristic” and an “oppressor” that had lost its “moral advantage.” Far from apologizing, Young declared, “I really don’t feel a bit sorry for anything that I have done.” In 2006, Young was asked again for his resignation, this time from a position with Walmart, after disparaging Jews, Koreans, and Arabs. In that instance, he did apologize.

According to Kramer, he reached out to Young for confirmation of Peretz’s account of the King dinner. It is perhaps telling that Young has not responded to confirm or deny King’s comments.

So what does this mean in regard to the relationship between African-Americans and American Jews, African-Americans and Israel, and Martin Luther King and Israel?

That King, during his lifetime, supported and admired the Jewish state is a matter of record, as was his concern for Israel’s security nine months after the 1967 War and only ten days before his assassination.

That King, during his lifetime, supported and admired the Jewish state is a matter of record, as was his concern for Israel’s security nine months after the 1967 War and only ten days before his assassination. In a March 25, 1968 conversation with Rabbis Abraham Joshua Heschel and Everett Gendler at the 68th Annual Convention of the Rabbinical Assembly for Conservative Judaism, King offered his most comprehensive comments on the subject, including consideration for the economic and social needs of Arabs. Among King’s comments was his disagreement with those who are “color-consumed” and who “see a kind of mystique in being colored.”

This must please anyone who admires the greatness of King. Still, it is what Martin Luther King believed 48 years ago, in life, long before so many historical, political, and ideological developments in the areas of race and society, social justice, and global relations. What would King think now?

That is the contest: To persuade the masses that King would have believed one thing or another. And since the enemies of Israel increasingly and, now, pervasively, abuse and construe Zionism as the essential demon seed of Western colonialism and nationalism, what little King said on the subject of anti-Zionism is a prize to be captured.

The contest for King—the import it would have to be able to argue that anti-Zionism is consistent with King’s legacy and revered memory as a social justice leader—is just one symbolic battle in the far-Left campaign to alienate Israel from the world and Jews from their historical identity. That campaign has advanced through many stages on multiple fronts. Race has always been at the forefront.

Consider that the anti-Semitic acme of the post-World War II era was UN resolution 3379, which declared that “Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination.” It was not just an attack on Zionism, not just a racist attack on the expression of Jewish identity in national liberation, but a declaration that Jewish identity in national liberation is in itself racist. What has followed, despite the ultimate revocation of 3379, has been a decades-long effort, not only by defunct communist regimes, not only by despotic Arab autocracies and theocracies, but by a vanguard of progressives and academics, to theorize away Jewish self-determination on racial grounds.

Today, this effort has moved into another sphere: The global social justice movement. Philosophizing global justice, however, is distinct from theorizing the political movement toward it. As Notre Dame associate professor Atalia Omer has written:

Symbolic declarations and gestures of co-resistance that expose cross-cutting matrices of domination by connecting the dots among seemingly disparate struggles for justice have indeed trended in US Palestine solidarity. Palestine solidarity, which has, of course, a familiar history in Islamist global mobilization and rhetoric (where solidarity is framed by underscoring sociocultural and religious affinities) has also gained traction as a secular, progressive cause, especially since the Call for BDS in 2005 issued by a host of groups comprising Palestinian civil society.

The far-Left political movement that sees itself as instrumental in actualizing global justice is steeped in theories of race and identity, bouncing between “intersectional” categories of it, tripping over hierarchies of oppression. All of this abstract thinking and high-minded activism is being mobilized not only against Israel, but against Jews, as we see in the case of American scholar Steven Salaita.

Salaita’s crudely anti-Semitic tweets were the least significant element in the withdrawal of a job offer by the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. What was significant were the reasons for the offer. Salaita’s academic career is now the exemplar par excellence of the movement to establish—via the concept of comparative indigenous studies, and employing those intersectional hierarchies of oppression—Palestinians as an indigenous people and anti-Israel advocacy as constitutive of a globally expanded understanding of indigenous identity. Specifically, an English professor with minimal study of more commonly understood indigeneity wrote a dissertation attempting to establish, on the basis of literary tropes, an identification between the settler-colonial founding of the United States and the founding of Israel. Labeling such scholarship “comparative” indigeneity, Salaita transformed into a professor of indigenous studies. While, in truth, these political movements represent a repeat colonization of indigenous culture by the West, this time, remarkably, via the cultural theorizing of far-Left academic elites, they also represent a globalization of anti-Zionist progressive justice advocacy.

There has been a decades-long effort by a vanguard of progressives and academics to theorize away Jewish self-determination on racial grounds.

Similarly, this globalization of anti-Zionism has recently been represented in actions seeking to identify the centuries-long history of slavery in America and continuing structural racism against African-Americans with the historical consequences for Palestinians of their rejection of the 1947 UN partition plan. In 2014, enemies of Israel equated the Ferguson shooting (and, more recently, the Black Lives Matter movement) to the Gaza war, thus tying the Missouri protests to the consequences of Hamas’s genocidal aspirations. The effort was aided at the time by a statement of Palestinian support for the Ferguson protests. A year later, this linkage was reversed via a statement of black solidarity with Palestine, with longtime activist Angela Davis and celebrated academic Cornel West as lead signatories. One of the two official organizers of the solidarity statement was Kristian Davis Bailey, a former student at Stanford of unrelenting Israel critic and BDS supporter David Palumbo-Liu. Said Bailey in a Salon interview with Palumbo-Liu, “We’re at a crucial moment in the global struggle against racism, in which the Black and Palestinian struggles play a crucial role.”

Such an apparently innocuous and generic statement of “peace and justice” activism provides a key insight into the reductive conceptualizing at work—racism formulated as a global political phenomenon, rather than as culturally distinctive and personally psychological in its development—in order to erase such hindrances as the particular history of Jews in the Middle East.

That this is a blatant distortion is shown, for example, by the fact that despite common origins in the European-originated Atlantic slave trade, the nature of racism in the democratic United States cannot be conflated with the discrete racial history of, say, Cuba, much less Russian racism against “Caucasians.”

Moreover, in light of the nine-century-long Arab- and Muslim-operated African slave trade, Palestinians may not be—on the clearly racialist consideration of dark skin tone and a mere six decades of military and political inferiority to another indigenous people with whom they contest for land—conflated with the American descendants of the African slave trade, in which Palestinians were as historically complicit as white Americans.

Anti-Zionism, the delegitimization of Jewish nationalism, is now central to far-Left global justice activism. Astonishingly, it has been made central by contradicting many of the most important ideas of post-colonial and critical race theorizing, among them, the valorization of colonized and oppressed indigeneity and the claim that race is a social construct.

Deconstructing the objective reality of race has meant, according to the American Anthropological Association (AAA), recognizing that the “‘racial’ worldview was invented to assign some groups to perpetually low status, while others were permitted access to privilege, power, and wealth.” What the AAA and its like decline to explore is that power is fluid and contextual. How else did Jews—the longest, most famously disempowered people in history—become, in their own nation-state, “powerful”? This gap in theorizing race in regard to oppressed peoples commonly portrays them as structurally incapable of racism themselves—except when it comes to Jews, who, by virtue of achieving national power, are now theorized as the activating global agent of racism, including in the U.S. Interestingly, the achievement of national power by Arabs and other post-colonial peoples is celebrated rather than condemned. Anti-Semitism, it seems, is more central to post-colonial theory than its adherents would like to admit.

Moreover, while race is critically deconstructed for groups of currently favored subaltern status, it is actively being reconstructed for Jews by non-Jews. This imposition on Jewish identity occurs in multiple forms: Denial of Jews’ indigeneity to their ancestral lands, genetically- and historically-based reassignment of Jewish identity, identification of Ashkenazi Jews as white Europeans (Jews’ own historic oppressors), suppression of the history of Sephardic Jews and of the reality of Mizrahi Jews, and willful ignorance of the uninterrupted presence of Jews in historic Palestine. The AAA, ignoring its own 1998 Statement on Race above, opens the “background” to its Israeli academic boycott resolution with reference to “Israel’s colonization of Palestine,” i.e. by denying Jewish indigeneity and reconstructing Jewish racial identity.

Anti-Zionism is now central to far-Left global justice activism, and has been made central to the movement by contradicting many of its most important ideas and theories.

In an era in which every other kind of racism is being analyzed with increasing theoretical depth in recognition of profound structural complexities, only anti-Semitism is regularly reduced by the same academics and activists to nothing more than time-honored tropes and preposterous libels: Simple slurs and stereotypes and avowed hatred. It is this theoretical turn, this concerted academic refusal to recognize anti-Semitism’s modern and sophisticated mutations that is the “new” anti-Semitism, which is itself one of those mutations. And we see it, too, in the effort each year to turn the spirit of Martin Luther King against Israel.

Just a few years into the controversy over “Letter to an Anti-Zionist Friend,” Tim Wise, an avowedly anti-Zionist Jew who presents himself as a professional “anti-racist,” weighed in on Electronic Intifada with his own effort regarding the “Misuse of MLK.” He holds in response to this “misuse” that all one can do is speculate about King’s future views, but he is otherwise at pains to diminish all of King’s positive statements about Israel. He then perorates with a list of what he now confidently asserts King would condemn and oppose, based on what seems “imminently [sic] clear from any honest reading of his work.” Apparently, what Wise means by misuse of King is any use other than that to which Wise would put him.

True misuse of King, it must be said, is using him at all, in all his totemic symbolism, as a weapon in contests beyond his lifespan. The record of the abuses to which the legacies of the great are subjected is long, and these debates only add to it. One might wish to rest assured about what so large a mind and spirit as King’s would have come to believe over time. He was a great man, with the magnitude of the adjective only amplified by remembrance of the noun. Yet the founders of the American republic, also men of astonishing greatness, did agree in their own lifetimes to a union founded in the legal protection of slavery and the non-personhood of the indigenous men and women of the land.

Had Martin Luther King, Jr., in a hypothetical completed life, come to mimic the hateful anti-Zionism of today, then he would have been tragically mistaken, to much sorrow. It is the ideas and their truth, not the men, that will out. What King did believe, and say, during his life, we know. We should all gratefully settle for it.

![]()

Banner Photo: Anthony Quintano / flickr