While Iran may seem diplomatically isolated, in Africa it has used unconventional tactics to support its terror network and build its nuclear program.

On the night of October 23, 2012, a military facility in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum erupted in a massive explosion. Video of the burning Yarmouk weapons depot revealed munitions streaming skyward, and white flashes going off amidst a burgeoning fireball. The explosion looked large enough to cremate anything it touched.

But satellite photos told a more interesting story. Three days later, the Satellite Sentinel Project, which uses satellite imagery to track human rights abuses in remote corners of Sudan, published a detailed before-and-after analysis of the incident. The “before” photos showed a small cluster of shipping containers piled next to a warehouse. In the “after” photos, the warehouse was barely scathed, while the shipping containers had been vaporized.

Well before the photographs’ publication, it was suspected that Yarmouk was an Iranian front, a vital link in funneling weapons to the Palestinian terrorist group Hamas. It was widely assumed that the explosion was the result of an Israeli air strike.

Though we don’t know what was inside the shipping containers apparently hit that night by the Israel’s air force, less than a month later the IDF undertook Pillar of Defense, November’s military operation targeting vast Hamas weapons caches in the Gaza Strip, and destroying the majority of the Islamist terrorist group’s long-range, Iranian-produced Fajr-5 rockets, which were used to strike as deep as Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. The Yarmouk incident might have been the opening salvo in an effort to neutralize a potentially game-changing new capability.

But Yarmouk was something far more dangerous than just a way station for illicit rockets.

A 2006 diplomatic cable published by Wikileaks singled out the facility for providing support to the Iranian and Syrian chemical weapons programs. And a detailed report from Conflict Armament Research found that the facility was manufacturing weapons of recognizably Iranian design, including small, portable rocket launchers.

Iran’s public diplomatic flubs often obscure its immense secret successes.

From one perspective, the bombing of Yarmouk is the residue of an Iranian strategic failure. Sudan is an ally, but it is a bad ally — one that can’t defend the airspace over its capital, and that is wracked with violent internal divisions and burdensome international sanctions related to the government’s atrocities in Darfur and the country’s south. Iran has been flummoxed in its efforts at building a real coalition of allies in Africa, despite repeated attempts at luring parts of the continent to its side — Iranian soft-power failures in Africa spans the continent, from Senegal to Comoros to South Africa. The last country openly embracing the Islamic Republic is a weak and unreliable pariah state.

But these failures bely Iran’s success planting footholds the for the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corp and Hezbollah, and they pose little threat to the Islamic Republic’s broader strategic goals.

In Africa, as in the Middle East, Iran has a longer game in mind. Even in the absence of any solid diplomatic alliances or victories, Iran is using its relationships in Africa to organize and advance its ambitious aims and terrorist networks. With its traditional diplomacy stifled, Iran has exhibited a worrying ability to overcome even Yarmouk-level setbacks — to accumulate asymmetrical victories for its aggressive, anti-western agenda.

By the standards of traditional diplomacy, Iran’s outreach in Africa has been disorganized and even amateurish. Iran has the global-level vision of a rising, self-styled superpower. The Islamic Republic clearly understands the need for alliances outside of its immediate neighborhood — and it appreciates the opportunities embodied in developing countries in need of cheap oil, foreign investment and powerful friends. The ambition is there, but Iran’s execution has been lacking. Senegal is a chief example: an economic and diplomatic push into one of West Africa’s most stable and powerful countries in the late 2000s included the opening of a jointly-owned automobile factory, and a series of presidential-level visits to Dakar and Tehran. But in what could be a glaring instance of Iran’s diplomatic objectives conflicting with its broader foreign policy, the Islamic Republic was caught facilitating the transfer of weaponry to rebels in Senegal’s south. Diplomatic relations were abruptly cut off in early 2011, and only recently resumed.

Iran’s failures in Comoros were less spectacular, but no less illustrative of the limits of the country’s traditional diplomacy. In 2009, it seemed as if Iran had made inroads into the tiny island chain off of the coast of Mozambique, the southernmost member of the Arab League. Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad visited Comoros as an “honored guest” in February of 2009, only underscoring how desperate Iran was for an African and Sunni Arab country it could win over to its side. But Iran’s outreach was so feeble that American diplomats actually started to mock it. In a March 2009 Wikileaks cable, a U.S. diplomat offered a biting assessment of a once-heralded military cooperation effort: “There have been bilateral agreements with Iran before — if the inoperable fishing boat in Moroni port is an example, there may be little to worry about.”

As researcher and Iran expert Ali Alfoneh explains, Iranian diplomacy is almost structurally dysfunctional, and is split between diplomats in the foreign ministry, and the powerful Revolutionary Guard. “In the case of the Islamic Republic, different government bureaucracies pursue their own goals which often are in conflict with the foreign policy objectives of other institutions,” he says. “The IRGC may have corporate objectives in [Africa], but those goals are not necessarily shared with the Foreign Ministry, or, for that matter, the Ministry of Intelligence.” One side of the Iranian foreign policy apparatus can decide that an alliance with a geopolitical lightweight like Comoros is a vital national interest — without even this very modest objective translating into policy.

There’s a clear disparity between Iranian goals in Africa, which reflect a maturing and globally ambitious foreign policy, and its ability to deliver on those goals, which reflect a self-image vastly out of proportion to Iran’s actual diplomatic abilities.

Soft power failures, however, are just one small aspect of a more alarming whole. For the Islamic Republic, every setback in conventional diplomacy masks its asymmetrical successes, which sometimes conflict with traditional diplomatic objectives. Using the territory of African countries to smuggle weapons to Hamas and Hezbollah might actually lose Iran UN votes, jeopardize its access to foreign markets, and harm its public diplomacy in the continent. The question is how much this actually matters when weighed against Iran’s ability to destabilize Lebanon, or to enable Islamist militants to fire rockets on Tel Aviv and Jerusalem.

Iran’s experiences in Sudan demonstrate how traditional diplomacy is subordinated to the Islamic Republic’s boarder, asymmetrical goals. Sudan’s Islamist National Congress Party (NCP)-led government signed a military cooperation agreement with Iran in 2008; according to The Telegraph, the IRGC maintained a base in Al Fashr, Darfur, as recently as September of 2011. The Conflict Armaments Research report strongly suggests that Iranian ammunition was used in at least some of the atrocities committed by Khartoum-allied militias during the conflict in Darfur, and that Sudan was a transit point for Iranian ammunition that eventually made its way to Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, on the other side of Africa.

This relationship is widely resented within Sudan itself. A significant faction within Sudan’s notoriously divided regime is set against a continued relationship with Iran, and in November of last year, foreign minister Ali Karti spoke out against the docking of Iranian warships in the Red Sea city of Port Sudan. According to one East Africa-based analyst who works frequently in Khartoum, the Sudanese government views its alliance with Iran as purely opportunistic. “It’s a very self-interested relationship,” he says. “In its propaganda, the NCP will talk about the infidel west, the Zionists, the communists, the atheists — and they will put the Shia in that list as well.”

For many Sudanese, the Yarmouk incident only demonstrated the cost of Sudan’s conscription into the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by its Iranian allies—a conflict which has nothing to do with Sudan’s own already-shaky internal affairs. “A lot of Sudanese are very upset, but not at the actual Israeli strike,” the analyst said. “They’re upset about the fact that the government is involving themselves in something that’s a lot bigger than what Sudan can handle.” Amongst some of Sudan’s leaders, and a significant part of its populace, Iran is an unwelcome ally. Even a fellow pariah state — truly an ally of last resort—harbors little real enthusiasm for the Islamic Republic and its policies.

But Iran has gotten exactly what it needs out of Sudan, regardless of how facile and opportunistic the ties between the two countries really are. Sudan is a beachhead for the IRGC — a transit point for weaponry that allows Hezbollah to aid in the Assad regime’s survival, and Hamas to rain Fajr 5s on the majority of Israel’s civilian population. It doesn’t matter that Sudanese resent the bombing of their capital city, or that Sudan is under international sanctions, or that Iran’s relationship with such a problematic country is liable to deepen perceptions of the Islamic Republic’s international isolation. All across the continent, Iran’s expansionist foreign policy is in direct conflict with its economic and soft power outreach—and Iran has succeeded is using Africa to advance its interests anyway.

South Africa, for instance, seems at first glance like a signal Iranian failure. Africa’s largest economy has totally caved to American and E.U. pressure on Iranian oil purchases, even despite the traditionally left-leaning foreign policy of the ruling African National Congress. In early June, the country’s Department of Energy announced that it had totally cut off its oil trade with Iran, and Trevor Houser of the Rhodium Group, which tracks the effects of sanctions on Iran’s oil sales, confirmed by email that “South African customs has not recorded any oil imports from Iran for several months now.”

Iran’s oil trade with South Africa may have dried up, but its deal with MTN allegedly gave it a major boost with the IAEA.

Iran’s oil trade with South Africa has evaporated, but the Islamic Republic scored a crucial consolation prize: a major investment from South African cell phone giant MTN, along with a raft of favors from the South African government. According to a civil complaint filed in District of Columbia federal court, MTN elbowed Turkcell, a Turkish competitor, out of a 49% stake in an Iranian joint venture called Irancell by “promising Iran that MTN could deliver South Africa’s vote at the International Atomic Energy Agency, promising Iran defense equipment otherwise prohibited by national and international laws, and the outright bribery of high-level government officials in both Iran and South Africa.”

The suit alleges that between 2003 and 2005, MTN won its Iranian license through a series of lucrative kickbacks. These consisted of straightforward bribes paid to Iranian officials, although the suit presents strong evidence that South Africa’s pro-Iran votes at the IAEA between 2005 and 2008 were a quid pro quo for the Islamic Republic’s approval of MTN’s Irancell investment. The complaint boasted over 60 pages of documentation, including damning internal emails leaked by an employee at MTN’s Tehran offices. It goes into specific detail about vehicles and military equipment the South Africans would provide to Iran if MTN were awarded the Irancell stake, a list which included “Rooivalk helicopters (based on the U.S. Apache platform), frequency hopping encrypted military radios, sniper rifles, G5 howitzers, canons…and other defense articles.” (The weapons were never delivered, and the Turkcell case was withdrawn in May of 2013–but only because the U.S. Supreme Court ruled a month earlier that international corporate civil suits could no longer be tried in U.S. court).

The scandal has resulted in no criminal prosecutions in South Africa. MTN still owns nearly half of Irancell, an arrangement that nets the company over $117 million a year. Irancell’s Iranian owner is a holding company whose investors include Iran Electronics Industries, a government-connected electronics and defense company that has been under U.S. sanctions since September of 2008. Iran and the IRGC are still leveraging their relationship with South Africa, even after the collapse of the companies’ oil trade. And according to Mark Dubowitz of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, the country is “a very hospitable place for Iranian sanctions-busting.” In early June, the U.S. Treasury Department added 37 Iranian front companies to its sanctions list. Three were based in South Africa.

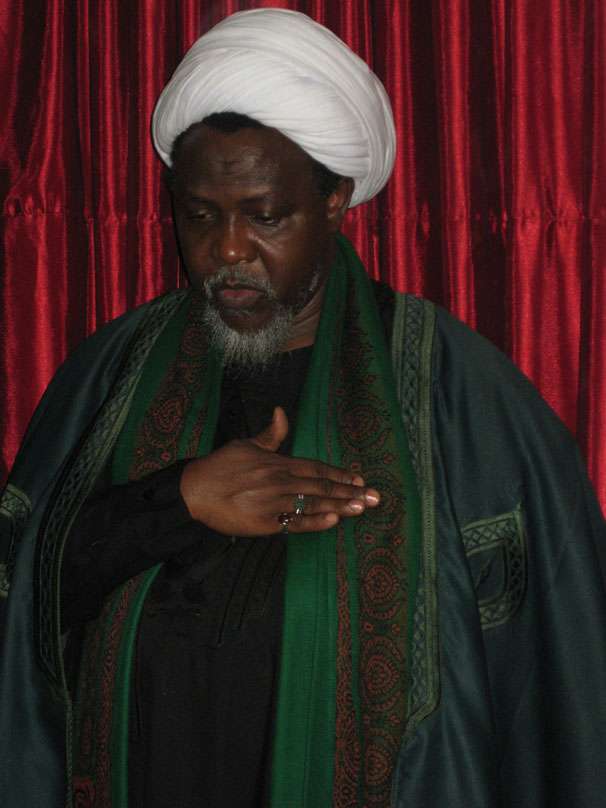

This pattern—in which Iran scrapes for asymmetrical gains within a challenging diplomatic environment, and in spite of its own internally divided conventional diplomacy—repeated itself in Nigeria. In October of 2010, Nigerian authorities scored the largest seizure of an Iranian weapons shipment in African history, when a container ship carrying crates of rocket launchers and heavy mortars was impounded in the port of Lagos. This embarrassment hardly ended Iran’s efforts in the country. In June of 2013, a Hezbollah cell was uncovered in the northern Nigerian city of Kano. And Iran has an asset in Nigeria that’s arguably more valuable than a foothold for its Lebanese proxies: Sheikh Ibrahim Zakzaky, a radical Iranian-trained Shi’ite cleric and a promoter of Iranian state ideology in Sub-Saharan Africa’s most populous country.

According to researcher Philip Smyth, Zakzaky’s career is the product of an Iranian recruitment effort in the early 1980s. “They approached him because he was leading various Islamist-style groups, and they told them if you come on board with us, you’ll have money and an ideology you can push.” He spoke out in favor of Khomeini-style clerical rule, and emerged as a leading hardliner during Nigeria’s late-90s debate over the imposition of Sharia law in the country’s predominantly Muslim north.

“Zakzaky was actually bitterly opposed to Sharia,” according to Alex Thurston, a PhD candidate at Northwestern University and an expert on Islam in Nigeria. “He said that this is just a half measure, and that you can only bring back Sharia if you do it in the context of a full Islamic state.” Thurston emphasizes that Zakzaky is a marginal figure in Nigeria — someone who commands tens of thousands of followers within a Muslim community of over 85 million. But he adds that Zakzaky has been a persistent and demagogical figure in Nigerian civic life. “He is known as a firebrand,” says Thurston. “He’s been in and out of jail through his career, and he’s extremely provocative when he’s on the radio.”

Perhaps significantly, there were almost no Nigerian-born Shi’ites in the country at the time of Iran’s Islamic Revolution, according to Thurston. A 2009 Pew Forum report said that there are as many as 4 million. Only a minority buys into hardline Khomeinism, but Zakzaky has still aided in Shi’ism’s spread in Nigeria. He is a careful and multilingual expositor of Iran’s state theology, and his skills were on full display during a 2009 lecture in London in honor of the 20th anniversary of Ayatollah Khomeini’s death. In Zakzaky’s view, Khoneimism had already triumphed over the revolutionary false consciousness of communism, and would deal a similar deathblow to western capitalism as well. “The Imam understood different aspects of the din [religion] as a universal message for the entire governance of mankind,” the Iranian-trained cleric said, in English, before closing his speech with a firm rejection of any kind of non-universalist, non-Khomeinist form of political Islam. “Some people think that just as we have imam Khomeini in Iran, other Muslim countries should have their own Khomeini-type leader…Look, the world, the whole world, the entire world needs only one Khomeini, and it has one.”

Iran has achieved at least a few of its asymmetrical objectives in Nigeria: it has an ideological foothold within the country’s Shi’ite community, which might include as much as 5 percent of Nigeria’s Muslims. And Hezbollah was able to sustain weapons caches and commercial interests in a country that, according to Smyth, has a notable Lebanese Shi’ite presence.

But perhaps the most startling Iranian success in Africa has to do with its pursuit of the ultimate asymmetrical objective: a nuclear weapons capability. Robert Mugabe’s regime in Zimbabwe inked a uranium agreement with Iran in 2011, and Ahmadinejad visited Niger, the world’s fourth-largest uranium producer, late in his second term as the Islamic Republic’s president. A 2006 Wikileaks cable asserts that Iran had smuggled Congolese uranium through ports in Tanzania. As for Tanzania—its government has proven remarkably tolerant of Iranian tankers operating under Tanzanian registration in order to evade the oil sanctions regime. Tanzania is a close enough U.S. ally to warrant a visit from Barack Obama during his July, 2013 trip to Africa. Iran can get what it needs even from African countries with established, pro-western bona fides—and despite an almost total absence of real friends in the continent.

As with its nuclear program, Iran has found its way around the obstructions that diplomacy and statecraft are constantly throwing in its path. Despite the pinch of international sanctions, and setbacks like the Stuxnet computer virus, Iran has increased the number of its operating uranium centrifuges, along with its stockpile of fissile material. Thanks to diplomatic stalling tactics, like the ones perfected by Iranian president-elect and former nuclear negotiator Hassan Rowhani, and its patient, decades-long accumulation of nuclear components, Iran has steadily progressed towards a nuclear weapons capability —even in the face of a nearly-global effort at derailing them.

In Africa, Iran has also found a way of overcoming its pariah status. The Islamic Republic is using Africa to extend Hezbollah’s reach, obtain nuclear material, advance its commercial interests, and arm its proxies in spite of the seemingly facile nature of what few diplomatic relationships it has in the continent. Yarmouk could offer a final, cautionary glimpse into Iran’s efforts in Africa. Eight months after Iran invited the ultimate embarrassment upon its Sudanese allies — namely, the bombing of its capital city — the Iranian-Sudanese relationship is still moving forward. In May, the Iranian military announced that it was increasing its cooperation with Sudan’s navy, and would even start training its African counterparts.

In its traditional diplomacy, Iran continues to possess the sophistication of a rising power, one that sees the necessity of building relationships on a global scale. Even if those relationships haven’t fully materialized, Africa provides worrying evidence of how little Iran really needs traditional alliances, or even competent international diplomacy, to get exactly what it wants.

![]()

Banner Photo: IDF