As we head towards another declaration of failure in the endless negotiations, Israeli life seems to rest forever on two contradictory truths: peace as an absolute necessity and an utter impossibility.

“One must be,” Goethe once said, “either hammer or anvil.” To this disturbing maxim, George Orwell later added the observation that, contrary to popular assumptions, it is the hammer that gets the worst of it. I have lived in Israel for over a decade, and have slowly developed the feeling that Goethe was wrong. In the face of Israel’s daunting challenges, in particular that of peace with the Palestinian Arabs, I often feel that to be Israeli is to be both hammer and anvil. And that much of our energy, political and otherwise, is dedicated to trying to figure out how to avoid getting the worst of it.

This feeling is never more acute than when what politicians and diplomats generally refer to as “painful concessions for peace” seem to be in the offing. With U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry supposedly about to present yet another framework for Israeli-Palestinian peace, the Palestinians expected to reject it, figures like Defense Minister Moshe Yaalon and Economics Minister Naftali Bennett warning that it will severely compromise Israel’s security and economy, and others like chief negotiator Tzipi Livni expressing a guarded optimism, now seems to be yet another of those times.

I do not think that I am alone in feeling this way. I have lived in Israel’s three largest cities—Beersheva, Jerusalem, and Tel Aviv—and have known Israelis whose politics run the gamut from extreme Left to extreme Right. Judging by my own observations, I think I probably speak for the majority of Israelis when I say that I often feel trapped by the insoluble dilemma of hammer and anvil. We hammer our enemies and, like the anvil, they seem to be relentlessly unmoved. Our enemies hammer us, and we remain stubbornly rooted in place.

This dilemma, I think, is defined by two essential things: the moral, political, and cultural weight of the continued occupation of the West Bank; and the fact that an Israeli withdrawal from the latter could well damage— perhaps severely—Israel’s national security.

Israel has occupied the West Bank for 47 years and, for the most part, no Israeli particularly liked it. Even most of those involved in the settlement movement, while eager to expand the Jewish presence in what was, after all, the heart of our ancient homeland for centuries, have rarely hailed the occupation itself. For the most part, Israelis have simply accepted it as a military necessity, providing Israel with strategic depth and the military presence necessary for effective interdiction of terrorism. Such sentiments were reinforced by the collapse of the Oslo Accords and the outbreak of the second intifada, which Israel only managed to defeat by expanding its military presence into areas from which it had previously withdrawn.

Yet there is little question among nearly all Israelis that the cost of retaining control of the area has come with a decidedly high price. It gobbles money that could be spent on infrastructure, social services, and military defense of Israel proper; it has demanded extensive military service and mortal sacrifice on the part of Israeli soldiers and families, sometimes in order to defend settlements they oppose; and it forces Israelis, whether they admit or not, into a moral dilemma deeply connected to their own past. Indeed, the last may be the most important. Despite the claims of Israel’s more fervent critics, most Israelis take little pleasure in exercising coercive power. Having been subject to the powerful for centuries, it would be effectively impossible for Israelis to feel comfortable with exercising such power over others. All of these factors were in play during the withdrawal from Gaza, which enjoyed the support of a majority of Israelis and which almost no Israeli, even those who believe it damaged the country’s security, wishes to reconstitute.

While the West Bank—for both strategic and ideological reasons—is a more complex situation than Gaza, a great many of the considerations involved still apply. One of the most important is that it presents two equally undesirable solutions short of a withdrawal from most of its territory.

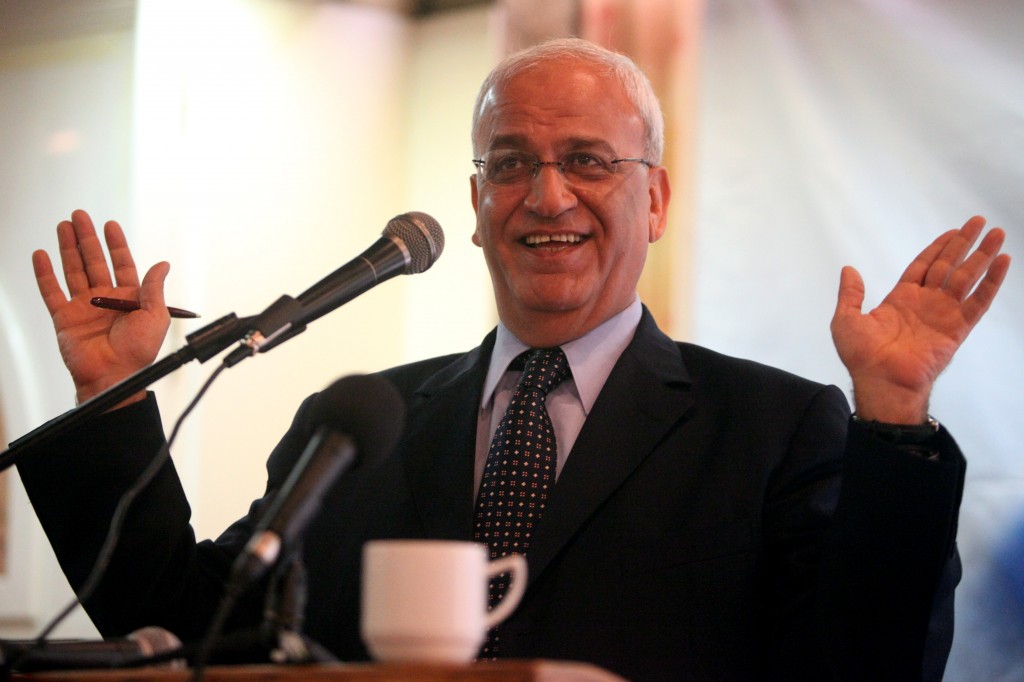

Saeb Erekat and Tzipi Livni at the 50th Munich Security Conference, January 31, 2014. Photo: Munich Security Conference / Wikimedia

The first is annexation. It is true that annexing the West Bank and grant the Palestinians equal rights, as some on the Right are now seriously proposing for the first time, would not immediately detonate the “demographic time bomb,” as many opponents of annexation have asserted. Nonetheless, it is a simple fact that, despite 40 years of the Jewish settlement movement, the Arab population of the territory massively outnumbers its Jewish counterpart. According to the CIA’s World Factbook, the estimated population of the West Bank in mid-2013 was 2,676,740. This includes 341,400 Jewish settlers; barely 13 percent of the total. Even if one adds the 196,400 Jews living in East Jerusalem, the total rises to only 20 percent. Approximately 80-90 percent of the West Bank, then, is Arab; an overwhelming majority that is unlikely to be surmounted anytime soon. A similar situation prevailed in Gaza, and as Ariel Sharon himself ultimately recognized: “We need to free ourselves from control over three-and-a-half million Palestinians, whose numbers are rising all the time.”

Annexation, then, would impose Israeli law and citizenship on a large territorial majority that wants neither. This would hardly constitute much of a solution. In fact, it would likely change nothing whatsoever. Israeli lives, treasure, and political capital would continue to be spent on what would essentially remain an occupation; the Palestinian Authority would be gone, Hamas would likely gain a decisive influence over the Palestinian population; and a third intifada would almost certainly erupt, to be followed almost as certainly by a fourth, a fifth, and so on.

This leaves a second, much darker option, which is essentially unthinkable to most Israelis: Expulsion. That this is undesirable is something of an understatement. Beyond its horrendous human cost, any attempt to expel the Palestinians from the West Bank would shatter Israel’s peace treaties with Jordan and Egypt, and severely if not fatally damage its relationship with the United States. It would also probably demolish our faith in ourselves, which is based at least partially on their own historical experiences of expulsion and exile. There is no doubt that both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict sometimes wish that the other side would simply disappear, but the idea of expulsion rightly horrifies all Israelis not completely corrupted by messianic fanaticism. It certainly horrifies me, and I know for a fact that I am very much not alone.

Head Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat shows the distance between the Israeli and Palestinian sides. Photo: Abir Sultan / Flash90

It seems, then, in a popular Hebrew phrase, ein breira; there is no solution to the problem of the West Bank but agreement to a Palestinian state or a unilateral withdrawal from most of the territory in question.

But such sureties are badly undermined by another part of the dilemma, one far less easy to surmount and admits of no clear answer. It is the ever-present question of Israel’s security. This has been presented to me several times—including by personal friends—in the form of a stark question: “Do you want missiles five minutes away from Ben-Gurion airport?”

Since one is immediately forced to answer “no,” this can often seem like a cheap scare tactic or a crude attempt at emotional blackmail. But it is not. It is a legitimate and deadly serious argument. The security of Israel’s eastern border, it holds, is essentially ensured by Israel’s continuing military presence in the West Bank, which interdicts attempts at terror, gathers intelligence on future attacks, prevents the deployment of missiles and other long-range weapons, and props up the relatively moderate Palestinian Authority.

Without such a presence, the argument goes, the Palestinian Authority will collapse and the West Bank will become a terrorist enclave, possibly controlled by the fanatical terrorist group Hamas, possibly by something even worse, such as al-Qaeda. In either case, the ruling party will be one that rejects Israel’s existence and continues to pursue a terrorist war against it. Given geographic realities, this would mean the emergence of a terrorist state bordering on Israel’s heavily populated central plain, poised to wreak havoc on Israel’s social and economic well-being. Economics Minister Naftali Bennett recently expressed exactly this fear in notably blunt language. “How will Israel’s economy look if a rocket falls in Shenkar Street in central Herzliya?” he asked, referring to the town where Israel’s high-tech industry blossomed. “What if once a year a plane crashes at Ben-Gurion airport?” he added, referring to the turkey shoot of airplanes daily lined up for a West Bank terrorist with shoulder-fired missiles.

Israeli Minister of Defense Moshe Yaalon (R) meets with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in Jerusalem on January 3, 2014. Photo: Matty Stern / Flash90

The Americans have recently tried to assuage some of these fears by proposing various “security arrangements” that supposedly ensure Israel’s safety even after the establishment of a future Palestinian state. That these proposals have failed to assuage the concerns of many Israelis is indicated by Defense Minister Yaalon’s recent undiplomatic remarks about Secretary Kerry. In Yaalon’s opinion—and he is certainly a man of long experience—“The American security plan presented to us is not worth the paper it’s written on. It contains no peace and no security. Only our continued presence in Judea and Samaria and the river Jordan will ensure that Ben-Gurion airport and Netanya don’t become targets for rockets from every direction.”

One can be forgiven for thinking that a large part of the resulting outrage directed Yaalon’s way was at least partially motivated by the fact that everyone knows he has something of a point. Indeed, his misgivings are predicated on recent historical experience: The aftermath of the Israeli withdrawal from Gaza. With all Israeli security assets completely removed, Gaza was quickly conquered by Hamas, and has become a base for continuing missile fire into Israeli territory. Once again, it is the numbers that tell the most chilling story. Rockets from Gaza have already succeeded in striking as far as Jerusalem, which is approximately 50 miles from Gaza. Only seven miles separate Ben-Gurion airport from the West Bank.

There is an argument to be made, of course, that if an agreement is reached, such a situation will not take shape, because Israel and a West Bank Palestinian state will have a formal peace treaty. This does not fill me—nor, I think, most Israelis—with a great deal of confidence. Even if a future Palestinian state does not fall to Hamas, such an agreement would still leave Israeli security dependent on the good will of Fatah, the party that refused peace in 2000 and then embarked on the terrorist war known as the second intifada, which killed hundreds of Israelis and did substantial damage to Israel’s economy. Given all this, most of us have come to think that there is a strong possibility that an Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank would lead not to less but more violence. Indeed, it is conceivable that it could lead to a war worse than the second intifada.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry hosts an Iftar dinner for Israeli Justice Minister Tzipi Livni and Palestinian chief negotiator Saeb Erekat at the U.S. Department of State in Washington, D.C., on July 29, 2013. Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia

Such an eventuality is not inevitable, but it is a very realistic possibility. This, of course, leaves us once again trapped in the same dilemma: A withdrawal from the West Bank would come with a very heavy economic, political, and human cost just as surely as not withdrawing from the West Bank.

Given all of this, Israelis can perhaps be forgiven for adopting an attitude of stoic despair. The dilemma of the West Bank, it often seems, cannot be resolved. The only solution is that there is no solution. Whatever we choose to do will threaten our survival. Under such circumstances, many of us think, the best we can do is to dig in, preserve stability as best we can, and see to our own progress and prosperity. There is nothing to be done but accept that we are perpetually trapped between hammer and anvil.

And yet, there is one indisputable fact that seems to indicate at least the possibility of cutting the proverbial Gordian Knot: Despite everything, the majority of Israelis continue to support a two-state solution in some form. Our enemies may wish to believe that we are an inherently brutal people, but this is an unjust claim; Israelis, by and large, like neither war nor occupation, and should anything like a genuine opportunity to divest ourselves of the West Bank present itself, I do not think the majority of Israelis would refuse to take the risk.

In fact, Israelis have already shown themselves willing to do so. When peace seemed possible at the end of the 1990s, Israelis voted for its primary advocate, Ehud Barak, in a landslide. Barak later made an unprecedented concessionary offer of peace to Yasser Arafat. Had Arafat not refused it, I have no doubt that Israelis would have supported its implementation, however painful.

Nor, I think, is the security argument ultimately sufficient to overwhelm this desire to ultimately end the occupation. Should a two-state solution fail to resolve the conflict and the Palestinians turn once again to war, it would not destroy Israeli society. Israel has already developed powerful and surprisingly effective defense systems, and they will likely grow more effective with time. And if the last decade has proven anything, it is that Israeli society is far from fragile; it has survived and even thrived despite being hammered by the most brutal and inhuman forms of violence.

To me—and judging by Israeli support, however uncomfortable, for a two-state solution, I am far from alone—there may not be a solution to the dilemma, but there is only one choice: We must be the anvil, absorbing and withstanding the persistent blows of our enemies, taking some comfort in the fact that the hammer, in the end, gets the worst of it.

![]()

Banner Photo: amvrosii/123rf